Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation at Georgetown: A Reckoning Made Possible by the Slavery and Justice Report

Let us begin with a clock.1

The curious, opening sentence of the Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice has stayed with me since I first read it in 2006, when I was a Brown Ph.D. student in American Studies. The document that grew out of President Ruth J. Simmons’ charge to the Committee, “to examine the University’s historical entanglement with slavery and the slave trade and to report [the] findings openly and truthfully,”2 artfully encapsulated this messy and layered task by pointing to Esek Hopkins’ clock. This object — formerly owned by Hopkins, the captain of the slave ship Sally, which was itself owned by members of the Brown family — prodded me, in my formative years as a scholar and a historian, to take notice of the plaques and portraits that adorn college campuses. Although I hadn’t seen that clock and its home in University Hall in nearly a decade, I immediately thought of it in the summer of 2015 when I joined my colleagues at Georgetown to take up a similar task to President Simmons’ mandate.

The Georgetown University Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation embarked on the process of identifying the visible and intangible ways that slavery’s legacies enveloped the University, founded by John Carroll in 1789. There were the obvious examples, such as the administration building named for Father Patrick Healy, an enslaved woman’s son who passed as white and became Georgetown’s twenty-ninth president. But there were also subtle parts of campus culture that harkened back to slavery’s importance. Georgetown students cheer for athletic teams wearing blue and gray-striped shirts, the school colors representing the period of reconciliation after the Civil War, a conflict in which Georgetown students fought on both sides. Most of the students educated at the College fought for the Confederate cause.

More than a decade after Simmons’ call at Brown, Georgetown undertook a similar project and quickly discovered that such a process would have been unimaginable without the Slavery and Justice Report. Georgetown’s work was also supported by University President John J. DeGioia, who was committed to expanding the narrative of the University’s history. The atmosphere in 2015 was infused with an urgency that forced the Georgetown community to link past and present on an anxious and often overwhelmed campus. We had one year to convene, study, and deliberate. Yet the Working Group’s tight timeline was, in many ways, not only the result of our internal deadlines, but also influenced by the urgency of students as they questioned the names on buildings, wore t-shirts memorializing the names of Black victims of racial violence, and paired their chants of “Black Lives Matter” with “Say Her Name.”

Let us begin with two names. At Georgetown, the reckoning with slavery was sparked by two buildings, one a modest one-story structure that once served as a stable, McSherry Hall; the other a multi-level Federal-style building adjacent to the heart of the campus, Healy Hall. The buildings, after being shuttered for years, were in the process of being redesigned and partitioned into modern, well-appointed student apartments. Like many campus buildings, they were named for two men who oversaw Georgetown in the 1830s, President Thomas Mulledy, S.J., and Superior of the Maryland Jesuits, William McSherry. Like many university buildings across the country, they were named for two men who were involved in the sale of human capital in the 1830s.

Just as the Hopkins clock had evaded much notice prior to Brown’s convening of the Slavery and Justice Committee, the names Mulledy and McSherry were rarely uttered on Georgetown’s campus after the buildings were retired from daily use. The section of campus where these buildings stood was known as the FJR — Former Jesuit Residence — a generic description of a specific sliver of the past. During the 2014–2015 academic school year, however, the campus newspaper’s historian, Matthew Quallen, visited the University archives and wrote a series of articles about Georgetown and slavery, including a moving piece about the Holy Rood Cemetery, an off-campus property where enslaved and free Black people were laid to rest.

President DeGioia asked the Working Group to do three things: “Make recommendations on how best to acknowledge and recognize Georgetown’s historical relationship with the institution of slavery, examine and interpret the history of certain sites on our campus, and convene events and opportunities for dialogue on these issues.”3 Similar to Brown’s process, our fifteen-member body met in subcommittees. Each subgroup signaled what we believed this work could do and many of the subgroups reflected the deliberations of Brown’s Committee: Local History to identify how Georgetown contributed to the District’s history of slave ports and emancipation movements; Archives to ensure that the history was preserved and prioritized in our University’s library; Ethics and Reconciliation to identify the present-day implications of racial repair; Permanent Naming to rechristen the dorms; Memorialization to ensure that the campus preserved the stories we uncovered and the ones that made us wonder; and Outreach to communicate why this work mattered. Community reactions ranged from simple shrugs to vociferous opposition to embarking on this work, lest we make Georgetown look bad. Some people wanted to split hairs between the University and the Jesuits — was it really Georgetown that owned slaves?

Georgetown did own slaves, and the majority of the Working Group’s research focused on the 1838 sale of enslaved people from plantations in Southern Maryland. Enslaved people were held as assets for Georgetown and the Jesuits at large, who, as members of a religious order, were not allowed to own property as individuals. The sale was “not the only, the first, or the last sale of slaves to provide operating revenue for the school, but it was the largest.”4 At the head of the sale were Mulledy and McSherry. The provisions of the sale conformed to the time period’s fantasy of a kinder and gentler human subjugation: The Jesuits indicated that the sale should preserve family groups as they were readied for sale to plantations in Louisiana, and the baptized would have their right to sacraments respected. The monies from the sale would not be used to relieve debts; rather, all proceeds would be placed in the University’s coffers for endowment purposes. The contemporary debates about the sale — from the Vatican’s support of gradual emancipation to the American Catholics who favored repatriation to Liberia — reminded those new to this history that the Jesuits, like all people who were afforded the right of owning other people, had options. A decision was made, a choice exercised. The men entered a sales contract with former Louisiana governor, congressman, and senator Henry Johnson and fellow slave owner Jesse Batey.

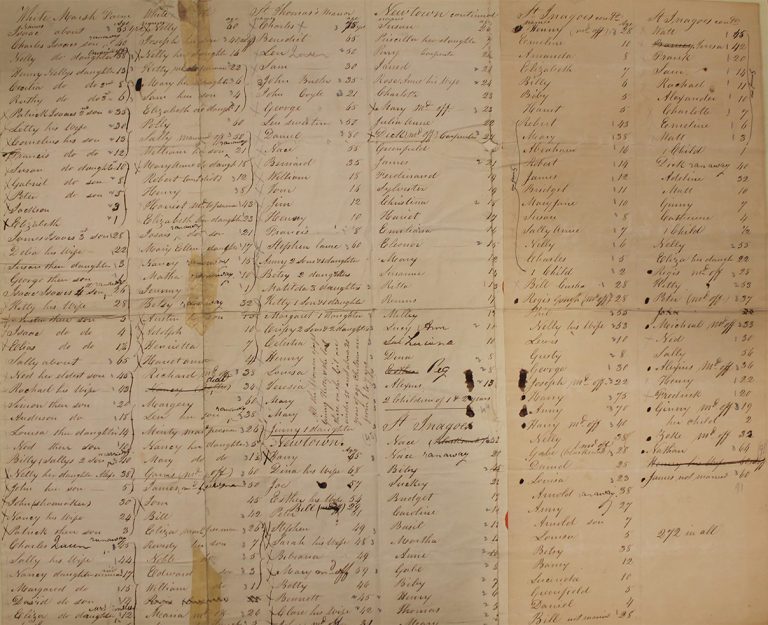

A list of men, women, and children sold by Thomas Mulledy in 1838, “272 in all,” with name, sex, age, family relationship, and plantation affiliation, also notes enslaved people who had run away and those who had been “married off.”

A copy of the “Articles of Agreement,” drafted by Mulledy, listed the price of the 272 slaves at more than $100,000, payable in installments over the following decade. The 272 were dispatched throughout Louisiana parishes, and their current community of descendants claim Maringouin, an Iberville Parish town of about 1,100 today, as where they see and feel their roots most vividly. The town’s name derives from the French word for mosquito, or, more specifically in this part of the world, swamp mosquito.

Universities are…conservators of humanity’s past. They cherish their own pasts, honoring forbears with statues and portraits and in the names of buildings.5

After a year’s worth of meetings, public events, and trips to the University archives, the Working Group submitted its Report of the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation to the President of Georgetown University in the concluding days of the academic year. I noted that our work began months after a white supremacist tragically took the lives of nine Black churchgoers attending Bible study in Charleston, South Carolina. And as we concluded our work, a candidate widely denounced as racist was seeking nomination by a major political party for President of the United States. My colleagues and I took a deep breath and busied ourselves with the work we had sidelined in order to complete the Report.

After we bid each other adieu, New York Times reporter Rachel L. Swarns reported on some stirrings at Georgetown. The university president and a few senior leaders had begun engaging a group of people who traced their family trees to Georgetown. These descendants of the enslaved people once owned by the Jesuits had offered emotional interviews, faded family photographs, and their perspectives on being Black and Catholic despite a history of racial betrayals from their beloved Church. Most, if not all, of the Working Group members were surprised to learn of this group’s identification with Georgetown and the University’s meeting with them. Soon, we would learn that our process — the painstaking editing sessions and the early-morning meetings — was incomplete because the voice of the descendant community had been missing from the process.

In the fall of 2016 — months before that candidate known for his demonstrations of racism was ultimately elected President of the United States — President DeGioia formally accepted the Working Group’s collective effort. The resulting document offered a history of Georgetown and slavery and a list of recommendations about what a university informed by the history of slavery could do, how it could act, and what its responsibilities were.6 Among the Report’s recommendations was an accepted proposal to rename Mulledy and McSherry Halls. The first was to be renamed for Isaac Hawkins, whose name is the first among the 272 slaves sold by Georgetown in 1838 and whose first name recalls the Biblical Isaac. The Old Testament story of Isaac’s near death at the hands of his father, Abraham, reminds the Georgetown community of the message of sacrifice and obedience to God. The second, which was to be named for Anne Marie Becraft, speaks to the world made by free people of color in Washington, DC, and honors a Black Catholic woman who built a school for girls outside the Georgetown campus and later became an Oblate Sister of Providence in Baltimore, joining the nation’s first African American female religious order.

The longer-term actions recommended in the Report included issuing an apology for the University’s participation in the sale and the nefarious trade in people more broadly, and connecting with the groups of people broadly defined as “descendants.” Before the printing of the final Report, the committee chair was able to include an acknowledgment of the people who trace their family roots to Georgetown, and who have since organized independent associations to connect, lobby the University to develop some type of reparative or restorative practice, and tell a richer story of Georgetown and slavery. The Working Group sought memorialization of the enslaved on the Georgetown campus, in the same vein as Brown’s commissioned piece, Slavery Memorial. Additionally, we advised that the group’s work should join the curricular and academic life of Georgetown through research, teaching, and public history initiatives. The Report endorsed a new framework for the University to think about ethics and morality in its current practices, from labor agreements to global activities. It also emphasized that the Working Group only focused on a sliver of Georgetown history — other symbols relating to slavery remained, including the statue of founder John Carroll and his mother Eleanor Darnall, both slave owners.

Members of the descendant community expressed their irritation at being on the outside of the Working Group. They were right. My fellow committee members wished we were told that this relationship was being forged between the descendant community and the University administration. Perhaps the University thought the bonds too fragile, the weight of history too heavy to share the charge, and was uncertain that we could act discreetly before Swarns’ article appeared. However, regardless of the reasons, the value of the Working Group’s research and recommendations is assessed as much by its exclusions as by its insights. After relying on the example set by Brown’s Slavery and Justice Report for more than a year, the Georgetown Working Group realized that, in the matter of connecting with the ever-growing number of people searching for a fuller story of their own history, we were now in a position to enter a new stage of our work. Brown’s legacy could be found in Georgetown’s early-stage work, but eventually, Georgetown had to write a new chapter on how universities and slavery pivot beyond research to repair.

One of the most elementary ways to repair an injury, though often one of the most difficult in practice, is to apologize for it.7

In a hall named for William Gaston, a Georgetown alumnus from North Carolina who owned humans for most of his life before renouncing slavery altogether, 100 members of the Georgetown slave descendant community celebrated a liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition, and Hope on Easter Monday of 2017. The service began with the singing of “Amazing Grace.” Timothy Kesicki, S.J., president of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, offered this apology for slavery: “We pray with you today because we have greatly sinned and because we are profoundly sorry.”

The day coincided with Washington, DC’s, annual Emancipation Day. The descendant community attended private meetings and a Mass with Jesuits, convening to discuss issues like reparations and to meet newfound family members. Guests shared reflections at tree plantings and dedication ceremonies; they wept and poured libations. The conviviality and camaraderie of the day have waned in the ensuing years. The descendant groups have organized into different bodies, with different goals. Some members of the community have enrolled as students on campus. Some campus staff members have traced their roots to the 272. Some wonder if they should submit to DNA tests or partner with genealogists to see if the rumors about their “folks back in Maryland” are indeed true.

People who suffer injuries and losses through the malicious or culpably negligent conduct of others have a right to redress — a right, as far as practicable, to be “made whole.”… But if the basic principle of reparations is straightforward enough, the application of that principle in specific cases is enormously complex. …8

After years of impatience for the full implementation of the Working Group recommendations, students decided to take up the work of addressing Georgetown’s relationship with slavery in their own ways. In the spring of 2019, flyers with lists of names of the 272 enslaved people of Georgetown’s past began to appear on campus. A new student group, a collective of undergraduate and graduate students named the GU 272 Advocacy Team, launched a campaign to create a student-financed Reconciliation Fund. The Fund — which was to be enriched by a proposed student fee of $27.20 per semester — was a gesture toward reparations, but the team avoided calling it reparations. Rather, they named the fund to touch upon the Catholic sacrament of confession. Reconciliation: the disclosure of sins in the interest of greater freedom; the resolution of debts; the meeting of two elements. As part of the Reconciliation Fund campaign, the names of Georgetown’s enslaved builders were used for campaign buttons. “For Charles”; “For Nelly.” Students diligently chalked all 272 names on sidewalks. The students were demanding justice for the people known only in archival records as “unnamed child,” “Gabe,” and “Biby.”9

The Advocacy Team used the student government’s referendum process to create a petition and subsequent ballot initiative that put the question of the Fund before their classmates and peers. At the heart of this proposal was the question of what students in the present owed those who suffered and toiled because of Georgetown in the past. No one action by the concerned students could answer that question, but the Advocacy Team saw their work as establishing the grounds on which students could contend with the connections between past and present. The proposal outlined what could happen if the Fund referendum passed. The program would be designed to be a direct cash aid program for anyone among the widening ranks of the descendant community, and the yearly fee would collect approximately $400,000 annually for applicants. The Advocacy Team suggested that those in need could use it for school expenses, healthcare, and rent assistance.

After months of organizing teach-ins, handing out flyers, and organizing interviews with the campus and national press, the Reconciliation Fund was put to a vote by the student body in April of 2019. A little over half of the undergraduate population were moved to vote in the referendum — an impressive percentage, based on prior elections. With nearly 67% of students voting affirmatively for the Fund — a little more than 3,000 students in total voted — Georgetown and slavery again became a topic of interest for journalists. In lieu of a statement of victory upon the announcement that the referendum had passed, the student organizers released an image of all 272 names, printed in white on a black background.

The votes, however, were not enough to declare victory. The new student fee would have to be approved by the University’s Board of Directors, and as students waited for the Board to determine whether this history-making initiative would come to fruition, the very idea of college students voting on reparations became a lively topic of debate. Mélisande Short-Colomb, a descendant who entered Georgetown as a first-year student in her sixties, became a student organizer of the Reconciliation Fund. Referencing the image of Jesus washing the feet of his apostles, she told Politico that “everything happens for students here on campus. If you can receive a benefit, are you not capable of extending a hand in service? … Are you capable of washing feet?”10 Some of Short-Colomb’s fellow descendants have called the students brave; others have called the students naïve, or believe the Fund makes the descendants appear in a demeaning light, as charity cases taken up by wealthy and privileged college students.

After months of waiting for the final decision on the Reconciliation Fund, students learned that the Board of Directors rejected the idea. In its place, the University committed to a series of initiatives to reach out to the descendant communities, in the form of a university-sponsored charitable foundation.11 By soliciting donations “from alumni, faculty, students and philanthropists,” the University shifted the Reconciliation Fund’s focus away from compelling all students to engage in a process of financial repair, and, in the view of Fund supporters, changed the spirit of the idea. How can a university take ownership of the consequences of slaveholding without requiring all members of its community to contribute? These are the types of questions that campuses can ask in the aftermath of Brown’s first foray into not only acknowledging the link between universities and slavery, but also making financial commitments to remedy the generational damage caused by it.

If this nation is ever to have a serious dialogue about slavery, Jim Crow, and the bitter legacies they have bequeathed to us, then universities must provide the leadership.12

Since the publication of this statement about universities and slavery, the landscape of higher education has changed. There are dozens of colleges and universities now studying slavery. Institutions founded after the abolishment of slavery are also using Brown’s Slavery and Justice Report to guide explorations on the harms done to Indigenous peoples; land theft at borders; gentrification; displacement; and medical racism. Regardless of the specificities of the harms done by individual universities, Brown has taught all of those who are invested in a transformative higher education that the past is ever-present and, like the ticking of a clock, sometimes requires us to truly listen in order to hear its sounds.