Confronting Historical Injustice: Comparative Perspectives

In her letter appointing the Steering Committee, President Simmons charged us not only to examine Brown’s history, but also to reflect on the meaning and significance of this history in the present. She particularly asked the Committee to examine “comparative and historical contexts” that might illuminate Brown’s situation, as well as the broader problem of “retrospective justice.” How have other institutions and societies around the world dealt with historical injustice and its legacies, and what might we learn from their experience? A substantial majority of the Committee’s public programs pertained to this aspect of our charge, to which we now turn.

Humanity in an Age of Mass Atrocity

Human history is characterized not only by slavery but also by genocide, “ethnic cleansing,” forced labor, starvation through siege, mistreatment of prisoners of war, torture, forced religious conversion, mass rape, kidnapping of children, and any number of other forms of gross injustice. Different civilizations at different historical moments have developed their own understandings of such practices, specifying the conditions under which they were allowed or forbidden and against whom they might legitimately be directed. Jews, Christians, and Muslims all devised rules for slavery, the conduct of war, and the treatment of prisoners and civilian populations. Our era is hardly the first to grapple with humanity’s capacity for evil.75

The idea that certain actions were inherently illegitimate and should be universally prohibited, no matter the circumstances or the particular target group, emerged in the eighteenth century. At the root of this belief was the idea of shared humanity, the belief that all human beings partook of a common nature and were thus entitled to share certain basic rights and protections. This conviction, which animated the early movement to abolish the slave trade, received its classic expression in the preamble to the American Declaration of Independence, with its invocation of “self-evident” truths about equality and inalienable rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Obviously, these rights have not been extended to all people at all times. As we have already seen, the idea of race, also a product of the eighteenth century, has played a particularly important role in blunting the claims of certain groups to full equality. Yet there is no question of the historical importance of the idea of shared humanity, which undergirds the whole edifice of international humanitarian law.

In bequeathing us the ideas of shared humanity and fundamental human rights, the eighteenth century also left us with a series of practical and philosophical problems. How are human rights to be enforced and defended? Do nation-states have the right to treat their own citizens as they please, or are there occasions when the demands of humanity trump national sovereignty? How are perpetrators of human rights abuse to be held to account? Such questions are obviously most pointed in the midst or immediate aftermath of atrocities, but they have longer-term implications as well, for great crimes inevitably leave great legacies. Are those who suffered grievous violations of their rights entitled to some form of redress, and, if so, from what quarter? Do such claims die with the original victims, or are there occasions when descendants might also deserve consideration? How do societies move forward in the aftermath of great crimes?

These are not merely academic questions. On the contrary, the global effort to define, deter, and alleviate the effects of gross historical injustice represents one of the most pressing challenges of our time. The modern era will go down in history as the age of atrocity, an age in which the fundamental human rights that most societies profess to cherish have been violated on a previously unimaginable scale. No single factor accounts for this grim reality. The birth of modern nation-states, with sophisticated bureaucracies and unprecedented industrial might; the creation of colonial empires; innovations in military technology; the rise of “total war,” involving the mass mobilization of civilian populations and the deliberate targeting of noncombatants; the growth of totalitarian ideologies; the emergence of ever more virulent forms of racial, ethnic, and religious bigotry; the rise of mass media, and the use of those media to foment hatred and fear: all these developments and more have radically enhanced humanity’s propensity and capacity for annihilation. Viewed in this context, the attempt to uphold basic principles of justice and humanity may seem a little like trying to hold back the tide, but few can doubt its urgency.76

Defining Crimes against Humanity

Broadly speaking, the history of efforts to restrain and redress the effects of gross human injustice has proceeded in two phases, both of which are of potential relevance to the current debate over slavery reparations in the United States. The first phase, stretching from the late eighteenth century to the aftermath of the Second World War, revolved around efforts to define and enforce international norms of humanitarian conduct in regard to three scourges: slavery and the slave trade; offenses committed during times of war; and genocide. These efforts reached a climax of sorts at Nuremberg, where an international military tribunal prosecuted the leaders of Nazi Germany, a regime that combined all the worst attributes of slavery, war crimes, and genocide. The second phase, beginning at Nuremberg and continuing to our own time, has focused less on prevention or prosecution than on redress — on repairing the injuries that great crimes leave. At the most obvious level, this entails making provision for the victims of atrocities and their survivors, but it also involves broader processes of social rehabilitation, aimed at rebuilding political communities that have been shattered.

Crimes against humanity are not simply random acts of carnage. Rather, they are directed at particular groups of people, who have been so degraded and dehumanized that they no longer appear to be fully human or to merit the basic respect and concern that other humans command. Such crimes attack the very idea of humanity — the conviction that all human beings partake of a common nature and possess an irreducible moral value. By implication, all human beings have a right, indeed an obligation, to respond — to try to prevent such horrors from occurring and to redress their effects when they do occur.

In both guises, retrospective justice rests on the belief that some crimes are so atrocious that the damage they do extends beyond immediate victims and perpetrators to encompass entire societies. The most common label for such offenses is “crimes against humanity,” a term meant to convey not only their great scope and severity but also their distinctive logic. Crimes against humanity are not simply random acts of carnage. Rather, they are directed at particular groups of people, who have been so degraded and dehumanized that they no longer appear to be fully human or to merit the basic respect and concern that other humans command. The classic example is the Holocaust, the Nazi campaign to exterminate Jews and other “subhuman” races, but the same logic can be seen in a host of other episodes, from the slaughter of more than a million Armenians by Turkish authorities during World War I to the systematic rape of more than twenty thousand Muslim women by Serbian soldiers in Bosnia in the 1990s. While obviously directed against specific targets, such crimes attack the very idea of humanity — the conviction that all human beings partake of a common nature and possess an irreducible moral value. By implication, all human beings have a right, indeed an obligation, to respond — to try to prevent such horrors from occurring and to redress their effects when they do occur. At the most obvious level, this means trying to prevent further bloodshed, to break the “cycles of atrocity” that crimes against humanity all too often spawn. But it also means confronting the legacies of bitterness, contempt, sorrow, and shame that great crimes often leave behind — legacies that can divide and debilitate societies long after the original victims and perpetrators have passed away.77

Slavery and the Slave Trade in International Law

The first international humanitarian crusade was the campaign to abolish the transatlantic slave trade, which stands historically and conceptually as the prototypical crime against humanity. As we have seen, Rhode Island played a conspicuous, if contradictory, part in the campaign, becoming the first state in the United States to legislate against the slave trade even as local merchants continued to play a leading role in the traffic. The movement’s crowning achievement came in 1807, when the British Parliament and the U.S. Congress both voted to abolish the transatlantic trade. While the United States made only a token effort to enforce the ban, Great Britain launched a major suppression effort, dispatching a naval squadron to the African coast and negotiating a series of bilateral treaties with other nations, permitting the boarding and inspection of vessels suspected of carrying slaves. Offenders were tried in special “Courts of Mixed Commission” scattered around the Atlantic World, an early example of the use of international judicial bodies to enforce humanitarian law. Africans redeemed from captured ships were taken to Freetown, in the West African colony of Sierra Leone, where they were settled in “recaptive” villages, each with its own school.78

It is difficult to appreciate, in retrospect, how remarkable this development was. In the course of a single generation, a commerce that had scarcely ruffled the world’s conscience for two and a half centuries was recast as a singular moral outrage. That the suppression campaign was led by Britain, the nation controlling the largest share of the transatlantic trade at the time, makes it more remarkable still. Yet the victory was less than complete. While the British Anti-Slavery Squadron apprehended hundreds of ships and liberated tens of thousands of people, it did not end the trade. Over the next half century, another two to three million Africans were carried to the Americas, chiefly to Cuba and Brazil. Equally important, the growing consensus on the criminality of the slave trade did not immediately extend to the institution of slavery itself, which continued to exist, and to enjoy wide acceptance, long after the trade had been banned. Britain abolished slavery in its colonies only in the 1830s, and it took another generation and a civil war to end the institution in the United States. In Brazil and Cuba, the last American nations to enact abolition, slavery survived until the 1880s.

The decade of the 1880s also saw the first multilateral anti-slavery treaties. At the Berlin Conference of 1885 and again at the Brussels Conference of 1889, delegates from fourteen nations — all the major European powers, plus the United States — solemnly pledged to use their offices to halt the trafficking of enslaved Africans, whether over land or water, anywhere in the world. But the rhetoric was deceptive, indeed rankly cynical. Alleviating the plight of enslaved Africans served as the chief rationalization for partitioning Africa into formal European colonies. While Britain and France came away with the greatest number of colonies, the single largest territory — the Congo Free State, an area equivalent in size to all of western Europe — was given as a protectorate to one man, King Leopold of Belgium. Over the next twenty years, Belgian officials in the Congo would oversee one of the most notorious forced labor regimes in human history in their relentless drive to produce more ivory and rubber. By the time Leopold was finally compelled to relinquish control of the territory in 1907, an estimated ten million people — about half of the population of the Congo — had died. It would take another two decades after that, until the 1926 League of Nations Slavery Convention, for the nations of the world to commit themselves formally to “the complete abolition of slavery in all its forms.”79

War Crimes

The year of the last documented transatlantic slaving voyage, 1864, also witnessed the first international treaty regulating the conduct of war, the Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies of the Field. Signers of the convention pledged not only to provide medical attention to enemy combatants, but also to refrain from firing upon hospitals, ambulances, and other medical facilities, provided that they were clearly marked — hence the treaty’s common name, the “Red Cross” agreement. Amended in 1906 and 1929, the convention was dramatically expanded after the Second World War to guarantee proper treatment of prisoners of war as well as the protection of civilians during times of war. (The terms of the 1949 agreements have recently come in for renewed debate, with American officials disputing their applicability to prisoners apprehended in the ongoing war on terror.) New protocols were added in 1977, extending protection to civilian victims of armed conflicts, including those waged within the borders of a single country.80

We can no longer afford to take that which was good in the past and simply call it our heritage, to discard the bad and simply think of it as a dead load which by itself time will bury in oblivion. The subterranean stream of Western history has finally come to the surface and usurped the dignity of our tradition. This is the reality in which we live.

The Hague Convention Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, signed in 1899 and extended in 1907, was more ambitious in scope but less effective in practice. The aim of the Convention was to establish basic rules of warfare, by prohibiting such tactics as the use of chemical weapons (chiefly poison gas) and aerial bombing. The 1907 convention also created a permanent court of arbitration, designed to resolve international disputes before they could escalate into war. The convention obviously did not achieve its objectives. It did not prevent the outbreak of World War I in 1914, nor did it deter belligerents from employing precisely the tactics they had renounced. While poison gas retained the odor of criminality, aerial bombardment soon lost it, and the practice was freely indulged by all sides in the Second World War, which ended with the deliberate incineration of civilian population centers. At the end of World War I, the victorious Allies made an effort to prosecute the leaders of Imperial Germany, bringing indictments against some eight hundred military and civilian officials for what were described as “war crimes” and “crimes against humanity.” But the postwar German government refused to hand them over, citing its precarious political position, and the Allies did not press the point. A small number of the accused were later prosecuted in German courts, but the few who were convicted escaped with light sentences, on the grounds that they had merely followed orders.81

Genocide

The aftermath of World War I also saw the first international confrontation with genocide, the systematic attempt to eradicate an entire group of people on national, ethnic, racial or religious grounds. While the term is of recent vintage — it was coined in 1944 by jurist Raphael Lemkin from the Greek word for race and the Latin word for killing — the process it describes reaches back to Biblical times and beyond. The colonization of the Americas offers a host of examples, from the destruction of the Taíno, the Caribbean islanders who greeted Columbus, to the slaughter of the Pequots in New England in the 1630s. The onset of European colonialism in Africa was also a genocidal business, as the exigencies of conquest intersected with racist ideology and imperial greed to produce murder on a mass scale. While the horror of the Congo Free State generated the greatest number of fatalities, the 1904–1907 Herero genocide in German South West Africa was in some respects more ominous, given German commanders’ expressed determination to bring about the “complete extermination” of people described as “nonhumans.” No one was ever prosecuted for the Herero genocide, which is today the subject of growing scholarly interest and a budding reparations movement.82

In the 1920s, Turkish courts convicted several perpetrators, in absentia, for their role in the “deportation and massacre” of Armenians, but the effort collapsed in the face of international indifference and resurgent Turkish nationalism. By the end of the 1920s, the official Turkish position on the matter was that the Armenian genocide had never occurred, a position upon which the government still insists today.

If colonialism represents one of the historical seedbeds of genocide, then total war represents another. In 1915, shortly after the outbreak of World War I, Turkish authorities launched a campaign to eliminate the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian minority. Over the next two years, an estimated one million Armenians were killed, while thousands of others were lost to their communities through deportation and forced religious conversion. These events were widely noted at the time, including by leaders of the Allied powers, who issued a joint declaration in May 1915 condemning the Turkish campaign and pledging to prosecute all responsible for these “crimes … against humanity and civilization.” Little ultimately came of that threat. In the 1920s, Turkish courts convicted several perpetrators, in absentia, for their role in the “deportation and massacre” of Armenians, but the effort collapsed in the face of international indifference and resurgent Turkish nationalism. By the end of the 1920s, the official Turkish position on the matter was that the Armenian genocide had never occurred, a position upon which the Turkish government still insists today. The lesson was certainly not lost on future genocidaires, including Adolph Hitler. “Who after all speaks today of the extermination of the Armenians?” he is reputed to have asked on the eve of the invasion of Poland.83

Nuremberg and its Legacy

Ultimately it took the horrors of World War II to compel the international community to face squarely the problem of crimes against humanity. In 1945, the Allied powers created a special tribunal to prosecute some of the men responsible for the horrors of Nazism. In a powerful symbolic gesture, the tribunal was convened in Nuremberg, the city in which the Nazis had first promulgated the “race laws” that stripped Jews of citizenship. In 1946, a second court, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, or Tokyo Tribunal, was convened to prosecute leaders of imperial Japan. Prosecutors and judges at Nuremberg and Tokyo were acutely aware of the unprecedented nature of the proceedings, which posed a variety of legal problems, not least deciding the specific charges on which perpetrators would be tried. They also appreciated the importance of their work in creating procedures and precedents for future generations facing the challenge of mass atrocity. Probably the most important accomplishment of the tribunals, and of Nuremberg in particular, was to establish that those who committed crimes against humanity could be held to account even when their actions were “not in violation of the domestic law of the country where perpetrated” — in short, that people were responsible for their conduct even when they acted “legally” or “under orders.”84

The primary institutional outcome of the postwar tribunals was the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, formally adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. The convention not only clarified and codified the still novel concept of “genocide,” but also committed signatories to taking concrete action to prevent and punish it, whenever and wherever it occurred. While prompted by the Nazi attempt to exterminate the Jews, the convention revealed the continuing importance of slavery and the slave trade as quintessential crimes against humanity. The list of offenses defined as constituting “genocide” included not only “enslavement,” but also forcible transfer of population, rape and other forms of sexual abuse, persecution on racial grounds, inhumane acts causing serious physical and mental harm, deprivation of liberty, and forced separation of children and parents. As one of the speakers hosted by the Steering Committee noted, had the Genocide Convention been in effect during the transatlantic slave trade or American slavery, signatories would have been obliged, at least in theory, to take action against them.85

International Humanitarian Law, National Sovereignty, and the United States

The tribunals created after World War II and the international conventions and protocols to which they gave rise represent watersheds in the history of international humanitarian law. Yet the tribunals have not fully realized the hopes of their architects, either in terms of deterring future atrocities or of prosecuting perpetrators. The rapid onset of the Cold War was a severe blow, making it all but impossible for the international community to mount any united response to murderous regimes, a weakness vividly displayed in the late 1970s, as genocidaires in Cambodia, Guatemala, and East Timor slaughtered millions with virtual impunity. At the same time, the growing emphasis on international responsibility under the auspices of the United Nations collided with still powerful ideas about the sovereignty of individual nation states. This problem became apparent immediately after the signing of the Genocide Convention, when the U.S. Senate refused to ratify the treaty. Though the intellectual and political foundations of the convention were chiefly laid by Americans, Senate opponents still balked at the prospect of U.S. citizens being tried before international tribunals rather than in American courts, where they were guaranteed certain constitutional protections. (The Senate finally ratified the treaty, with reservations, in 1988, forty years after its drafting.)86

Prospects for collective action have improved somewhat since the end of the Cold War. While the international community was fatally slow to acknowledge and respond to the outbreaks of genocide in Rwanda and Bosnia in the early 1990s, the appointment of international criminal tribunals for both cases revives hope that at least some murderers will be punished for their crimes. More recently, special “hybrid” tribunals, blending elements of national and international judicial systems, have been appointed to prosecute surviving perpetrators of the Cambodian and East Timorese genocides, as well as those responsible for more recent atrocities in Kosovo and Sierra Leone. Maintaining a multiplicity of courts, each with its own personnel and procedures, has inevitably produced complications and delays, but together these tribunals bespeak a new international determination to hold perpetrators of gross human rights abuse to account. In 1998, delegates from 140 nations signed the Rome Statute establishing a permanent International Criminal Court dedicated to investigating and prosecuting genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, but the court’s stature and effectiveness remain unclear. In 2002, the United States formally withdrew its signature from the accord, again citing the issue of national sovereignty, as well as concerns that the court might be used to arraign American civilian and military personnel.87

At the time of writing, the primary challenge to the international humanitarian regime lay in Darfur, a region in western Sudan that is the site of an ongoing genocide. Whether the international community has the capacity and will to stop the killing or to bring those responsible to justice remains to be seen.

The Limitations of Retributive Justice

The tradition begun at Nuremberg and continuing in the various international tribunals operating today represents a form of what is known as retributive justice. Justice, in this view, centers on punishing evildoers. Historically, this is the most common form of justice and it is generally uncontroversial. But it has limitations. It is time bound. While crimes against humanity are generally excluded from statutes of limitation, prosecution is obviously only possible while perpetrators live. It also raises questions about selectivity. In a world rife with injustice, how do we determine which offenses are sufficiently grievous to require prosecution? And how do we determine whom specifically to prosecute? In the Nazi Holocaust, hundreds of thousands of people, virtually an entire society, became implicated in genocide, yet the original Nuremberg trials featured only two dozen defendants.88

These problems point to others. Crimes against humanity typically involve not only large numbers of perpetrators but also vast numbers of victims, with a range of different injuries, some of which persist for generations. While seeing perpetrators in the dock may bring some satisfaction to victims or their descendants, it does little in itself to rehabilitate them, to heal their injuries or compensate them for their losses. More broadly still, approaches focused solely on prosecution do little to rehabilitate societies, to repair the social divisions that great crimes inevitably leave. In other words, crimes against humanity raise issues not only of retributive but also of reparative justice.89

Reparative Justice and its Critics

As in the case of retributive justice, the history of reparative justice efforts is closely associated with the Holocaust. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the government of West Germany, spurred in part by pressure from the United States, launched a series of programs intended to repair at least some of the damage wrought by Nazi atrocities. The West German effort, which included a formal acknowledgment of responsibility by the prime minister on behalf of the German people, as well as the payment of substantial reparations to victims, remained a more or less isolated example during the decades of the Cold War; but in the years since the 1980s, the world has seen a proliferation of reparative justice initiatives, stretching from Argentina to Australia, South Africa to Canada. While it is too early to assess the long-term effects of many of these programs, the idea that victims of crimes against humanity are entitled to some form of redress is today a more or less settled principle in international law and ethics. This status was confirmed with the publication in 2003 of the United Nations’ “Draft Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Violations of International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law.”90

Not everyone has welcomed these developments. In every society, there are many people who dismiss the whole reparative justice project as divisive, foolish, or futile. In the United States, such criticisms have emanated from both ends of the political spectrum. For some on the right, the quest for historical redress, and for monetary reparations in particular, is just one more symptom of the “culture of complaint,” of the elevation of victimhood and group grievance over self-reliance and common nationality. For some on the left, the preoccupation with past injustice is a distraction from the challenge of present injustice, a reflection of the “decline of a more explicitly future-oriented politics” brought about by the collapse of socialist and social-democratic movements around the world. Advocates of reparative justice offer several rebuttals to these criticisms. Far from fomenting division, they argue, confronting traumatic histories offers a means to promote dialogue and healing in societies that are already deeply divided. This process, in turn, can generate new awareness of the nature and sources of present inequalities, creating new possibilities for political action. Viewed in this light, reparative justice is not an invitation to “wallow in the past” but a way for societies to come to terms with painful histories and move forward.91

The notion of reparative justice has attracted criticism from both ends of the political spectrum. For some on the right, the quest for historical redress is just one more symptom of the “culture of complaint,” of the elevation of victimhood and group grievance over self-reliance and common nationality. For some on the left, the preoccupation with past injustice is a distraction from the challenge of present injustice, a reflection of progressive paralysis following the collapse of socialist and social-democratic movements around the world.

While recent discussions of slavery reparations in the United States have chiefly focused on monetary payments, the history of reparative justice initiatives around the world suggests a wide variety of potential modes of redress. Broadly speaking, these approaches can be grouped under three rubrics: apologies (formal expressions of contrition for acts of injustice, usually delivered by leaders of nations or responsible institutions); truth commissions (public tribunals to investigate past crimes and to create a clear, undeniable historical record of them); and reparations (the granting of material benefits to victims or their descendants, including not only money but also nonmonetary resources such as land, mental health services, and education). Conceptually distinct, these approaches often overlap in practice. The 1988 U.S. Civil Liberties Act, for example, combined all three modes in addressing the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, including a national commission to study the matter and collect public testimony, modest monetary reparations ($20,000 to each surviving internee), and a formal apology, tendered by the President on behalf of the nation.92

Apology

One of the most elementary ways to repair an injury, though often one of the most difficult in practice, is to apologize for it. In 1951, West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer issued a formal statement acknowledging the responsibility of the German people for the crimes of the Holocaust. The statement, produced after long and rancorous negotiations, was something less than an unqualified apology. “The overwhelming majority of the German people abhorred the crimes committed against the Jews and were not involved in them,” Adenauer insisted, adding that many had risked their lives “to help their Jewish fellow citizens.” “However,” he continued, “unspeakable crimes were committed in the name of the German people, which create a duty of moral and material reparations.” While tentative, Adenauer’s acknowledgment of responsibility, together with his government’s agreement to pay substantial reparations to victims of Nazi persecution, represented a crucial step in Germany reclaiming its status within the community of nations. It also sharply distinguished the West German government from its counterpart in communist East Germany, which disclaimed any connection to or responsibility for the crimes of the Nazi regime.93

In 1951, the idea of a representative leader of a nation or institution formally taking responsibility for the offenses of predecessors was a novelty. Today, examples abound. In 1995, Queen Elizabeth II became the first British monarch to issue a formal apology to her subjects, directed to the Maori of New Zealand, for “loss of lives [and] the destruction of property and social life” occasioned by British colonization. In 2000, Pope John Paul II used the occasion of the first Sunday of Lent to apologize and “implore forgiveness” on behalf of the Catholic Church for a long catalogue of sins, including the violence of the Crusades and Inquisition, the humiliation and marginalization of women, and centuries of persecution of Jews. In 2005, ninety-two U.S. Senators endorsed a resolution formally apologizing for the Senate’s role in abetting the lynching of African Americans by refusing to enact a federal anti-lynching statute. The list goes on.94

…[C]ivilization discovered (or rediscovered) in 1945 that men are not the means, the instruments, or the representatives of a superior subject — humanity — that is fulfilled through them, but that humanity is their responsibility, that they are its guardians. Since this responsibility is revocable, since this tie can be broken, humanity found itself suddenly stripped of the divine privilege that had been conferred on it by the various theories of progress. Exposed and vulnerable, humanity itself can die. It is at the mercy of men, and most especially of those who consider themselves as its emissaries or as the executors of its great designs. The notion of crimes against humanity is the legal evidence of this realization.

Several speakers hosted by the Steering Committee discussed the recent proliferation of national and institutional apologies, offering sharply different analyses. Some were critical, dismissing the wave of recent apologies as a vogue, “contrition chic,” the triumph of the therapeutic and symbolic over the political and substantive. What can an apology possibly mean, one asked, when the people offering it neither enacted nor feel directly responsible for the offense for which they are apologizing, and when the people accepting the apology did not directly experience the offense? Others defended apology as an essential aspect of historical redress, particularly when accompanied by some material demonstration of seriousness and sincerity. Far from just “cheap talk,” they argued, apologies offer an opportunity to facilitate dialogue, nurture accountability, and enrich political citizenship. As one speaker noted, most atrocious crimes in history begin with the denial of the equal humanity of a certain class of people; thus any project of social repair must begin with some acknowledgment of the dignity of that group and of the seriousness of what they suffered. Apologies are one vehicle to accomplish this.95

The Politics of Apology: Australia’s “Stolen Children” and Korean “Comfort Women”

As several speakers noted, apologizing can be a complicated business. As in relations between individuals, apologies between groups and institutions involve subtle assessments of sincerity and motive, timing and tone, all of which are inevitably complicated by the variety of actors and the passage of time. The case of abducted Australian Aboriginal children, the subject of one of the programs sponsored by the Steering Committee, offers a dramatic example. Between 1900 and the early 1970s, the Australian government, working with Christian missions, removed an estimated one-hundred thousand Aborigine children from their families and consigned them to boarding schools and white foster families as part of a forced racial assimilation policy. (The policy focused on light-skinned, or “half-breed,” children; full-blood Aborigines were presumed to be unassimilable and destined for extinction.) In the 1980s and ’90s, the fate of the “stolen children” became an important political issue in Australia, culminating in the appointment of a government commission of inquiry; the commission, which issued its report in 1997, recommended a formal government apology to affected families.96

The commission’s recommendation was rejected by the newly elected conservative government of John Howard, who insisted that current Australians bore no responsibility for the sins of their forebears and should not “embroil themselves in an exercise of shame and guilt.” The prime minister also expressed fears that an official apology would lead to massive compensation claims against the Australian government. Howard’s position prompted an immediate outcry, leading to the passage of apology resolutions in several state parliaments and the organizing by community groups of an annual “National Sorry Day.” The groundswell prompted Howard to amend his position, and in 1999 he introduced a resolution that expressed “deep and sincere regret” for the forced assimilation policy, but also stopped short of apologizing or accepting responsibility for it. The controversy continues today.97

The politics of apology have been even more contentious in East Asia, where the conduct of the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II — and the refusal of subsequent Japanese governments to accept full responsibility for that conduct — continues to shadow relations between Japan, China, and North and South Korea. Over the last fifteen years, Japanese leaders, including the current emperor and the prime minister, have issued numerous statements expressing regret and contrition for wartime atrocities, but the belatedness of the statements and their emphasis on personal remorse rather than collective responsibility have left many victims groups distinctly unsatisfied. The controversy has come to focus on the predicament of so-called “comfort women” — women and children from Korea, China, and other occupied territories who were abducted from their homes and forced to work as sex slaves in military brothels. In 2001, after more than half a century of denial, the Japanese government acknowledged “military involvement” in the system and offered survivors up to $20,000 in “atonement” money from a privately funded “Asian Women’s Fund.” But a group of surviving comfort women, mostly from Korea, rejected the money, insisting that any funds should come directly from the Japanese government, accompanied by an unequivocal acceptance of responsibility and a formal apology.98

In the American case, skepticism about institutional apologies reflects not only deeply ingrained beliefs about individual responsibility but also wariness of the nation’s litigious culture. In the United States today, there is a widespread sense that to apologize for or even to acknowledge an offense exposes one to legal liability and invites claims for damages.

The comfort women controversy is doubly relevant here, because the case has become a political issue in the United States. Outrage over the treatment of the women was the main inspiration for the Lipinski Resolution, a joint U.S. Congressional resolution introduced in 1997 which called upon the government of Japan to “formally issue a clear and unambiguous apology for the atrocious war crimes committed by the Japanese military during World War II; and immediately pay reparations to the victims of those crimes.” The resolution attracted dozens of congressional sponsors but was eventually scuttled by the State Department, chiefly because of concerns that it would encourage other reparations claims. In April 2006, another joint resolution was introduced into Congress, again calling upon the Japanese government to “acknowledge and accept responsibility for” the enslavement of comfort women, and also to take steps to “educate current and future generations about this horrible crime against humanity.” The bill, which is pending, omits any reference to reparations, though it enjoins Japan to “follow the recommendations of the United Nations and Amnesty International with respect to the ‘comfort women’” — recommendations that include payment of monetary reparations.99

National Apologies in the United States

Leaving the question of monetary reparations momentarily aside, there is a distinct irony in demands for a governmental apology coming from Americans, who tend to be skeptical of the value of collective apologies for past wrongs, at least when their own history is concerned. As innumerable letters sent to the Steering Committee made clear, many Americans reject, indeed resent, the suggestion that they bear some responsibility for actions in which they took no part, actions that may have occurred before they were born. The very notion collides not only with deeply ingrained beliefs about individual responsibility, but also with quintessentially American ideas about historical transcendence, the capacity and fundamental right of human beings to shake off the dead hand of the past and create their lives anew. This skepticism is reinforced by the nation’s litigious culture. In America today, there is a widespread sense that to apologize for or even to acknowledge an offense exposes one to legal liability and invites claims for damages.

Despite these constraints, there are several examples in recent American history of government apologies. Japanese Americans forcibly interned during World War II received a presidential apology — in fact three: one from Gerald Ford in 1976, one from Ronald Reagan, when he signed the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, and one from his successor, George H.W. Bush, when implementing the act. In 1993, Bill Clinton issued a formal apology to the Indigenous people of Hawaii for the American government’s role in the destruction of Hawaiian sovereignty. Four years later, Clinton apologized to victims of the Tuskegee “Bad Blood” experiment, in which the U.S. Department of Health deliberately and deceptively withheld treatment from African Americans infected with syphilis in order to study the effects of the unchecked disease. The 2005 Senate resolution on lynching represents the most recent example of a government apology, though it was offered on behalf of a particular institution rather than of the nation as a whole.100

Apologies Untendered: Native Americans and African Americans

American leaders have been notably slower to extend apologies to the two groups who would seem to have the most obvious claims to them: Native Americans and African Americans. While the Indigenous people of Hawaii have received a presidential apology, native peoples on the mainland have not. In 2000, the Bureau of Indian Affairs apologized for its role in the “ethnic cleansing” of native lands and the deliberate annihilation of native culture, but the gesture’s impact was muted by the fact that it came from an assistant secretary of the Department of Interior, on behalf of a government agency, rather than from the President, on behalf of the nation. (The fact that the official who issued the apology was himself Native American further reduced its effect.) In 2004, a trio of senators, led by Ben Nighthorse Campbell, a Republican from Colorado and member of the Northern Cheyenne tribe, introduced a joint Congressional resolution to “acknowledge a long history of official depredations and ill-conceived policies by the United States Government regarding Indian tribes and offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the United States.” But the bill received a negative recommendation from the Senate’s Committee on Indian Affairs and died without reaching the Senate floor.101

The government has been even more reticent on the subject of slavery. While a growing number of American churches, corporations, and universities have acknowledged their complicity in slavery and the slave trade, the nation as a whole has not. In 1997, Congressman Tony P. Hall of Ohio introduced a one-sentence concurrent resolution — “Resolved by the House of Representatives that the Congress apologizes to African Americans whose ancestors suffered as slaves under the Constitution and the laws of the United States until 1865” — but the bill languished in committee without ever coming up for debate on the floor of Congress. In the meantime, the closest the U.S. government has come to a formal apology is a pair of statements by President Clinton in 1998 and President Bush in 2003, both delivered at the same spot: the old fortress at Goree Island in Senegal, West Africa. Both presidents expressed regret for the slave trade, but they also carefully stopped short of apologizing for it. President Bush gave a particularly stirring speech, describing the slave trade as “one of the greatest crimes of history” and slavery itself as “an evil of colossal magnitude,” the latter characterization borrowed from his eighteenth-century predecessor, John Adams. Yet he offered no apology, nor any suggestions about what Americans in the present might do in light of this painful history. Whether the bicentennial of the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade in 2007 will provide the occasion for a more forthright apology remains to be seen.102

Telling the Truth

If there is a single common element in all exercises in retrospective justice, it is truth telling. Whether justice is pursued through prosecution, the tendering of formal apologies, the offering of material reparations, or some combination of all three, the first task is to create a clear historical record of events and to inscribe that record in the collective memory of the relevant institution or nation.

In 1997, a Congressman from Ohio introduced a one-sentence concurrent resolution apologizing for slavery: “Resolved by the House of Representatives that the Congress apologizes to African Americans whose ancestors suffered as slaves under the Constitution and the laws of the United States until 1865.” The bill died without coming up for debate on the floor of the House.

Of course, the truth is not always easy to discern. Most crimes against humanity are sprawling events, unfolding over months or years and involving vast numbers of actors, who often have very different perspectives, both at the time and in retrospect. Documentation is often in short supply, sometimes because records were not kept, sometimes because they were deliberately destroyed. Even the Holocaust, the most thoroughly organized and documented genocide in human history, has proved to be an elusive affair. Historians today estimate that only about half of those who perished under the Nazis died in death camps, the balance having been shot, stabbed, beaten, worked, or marched to death in a myriad of individual acts of atrocity. Even today, more than sixty years later, historians continue to uncover details of killings long forgotten or suppressed, including most recently a series of murderous pogroms launched by Poles against their Jewish neighbors, some after the war was over.103

As such revelations suggest (and as the controversy they have unleashed abundantly confirms), not everyone wishes to have the full truth told. As a general rule, perpetrators and their associates are particularly anxious to see societies “turn the page” on the past. But even after perpetrators have left the scene and the immediate threat of prosecution or retaliation has receded, the idea of unearthing the past often confronts significant opposition from people who fear that such inquiries may threaten their social standing or undermine cherished national myths. Both of these motives can be seen in the Turkish government’s continuing insistence that the Armenian genocide of 1915–1917 never happened, a claim flatly contradicted by thousands of eye-witness accounts, newsreel footage, and an abundant documentary record. (Under current Turkish law, anyone asserting that the genocide occurred is liable to prosecution for the crime of “denigrating Turkishness,” an offense punishable by up to three years in jail.) This is obviously an extreme example, but the same impulse to evade, extenuate, or deflect the full burden of the past can be seen in many other cases, from Konrad Adenauer’s insistence that the vast majority of Germans had “abhorred” Nazi crimes and played no part in them to the time-honored refrain in New England that slaves in the region were treated kindly.

History and Memory

As these examples show, the struggle over retrospective justice is waged not only in courts and legislatures but also on the wider terrain of history and memory — in battles over textbooks and museum exhibitions, public memorials and popular culture. The Steering Committee organized many programs around these issues, on topics ranging from the design of Holocaust memorials to the efforts of some citizens of Philadelphia, Mississippi, to come to terms with the murder of three civil rights workers in their community in 1964. Many of these programs focused on the history and memory of American slavery, the focus of the Committee’s charge. Speakers discussed the erasure of slavery and the slave trade from New Englanders’ collective memory; the history and mythology of the Underground Railroad; representations of slavery in twentieth-century African American art and literature; the politics of slavery reenactments at historical sites like Colonial Williamsburg; and popular reactions to recent DNA tests that appear to confirm long-standing allegations that Thomas Jefferson fathered children by one of his slaves, Sally Hemings. While different speakers offered different conclusions, all agreed that slavery remains an extremely sore subject for many Americans, white as well as Black. If one of the defining features of a crime against humanity is the legacy of bitterness, sensitivity, and defensiveness that it bequeaths to future generations, then American slavery surely qualifies.

Commissioning the Truth

The Steering Committee also organized several programs on truth commissions, which have emerged in recent years as one of the primary mechanisms for societies seeking to come to terms with atrocious pasts. The best-known example is the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, established in 1995 during that country’s transition from racial apartheid to democratic rule, but South Africa is far from alone. Since 1982, at least two-dozen countries have convened truth commissions of one sort or another. While the United States government has never formally convened a truth commission, the model has been used at the national, state, and even municipal level to examine specific historical injustices.

Though the particulars differ, truth commissions typically share certain features. Almost by definition, they are convened in societies that have seen massive violations of human rights, usually perpetrated by the state or its agents, thus creating a need for some kind of extraordinary body, beyond the normal system of judges and courts, to address them. Not surprisingly, they are usually associated with periods of political transition, as societies struggle to erect new, legitimate governments atop the ruins of old, discredited ones. At the same time, they tend to occur in societies in which leaders of the old regime continue to exercise substantial power, rendering prosecution impractical. In some cases, truth commissions have been part of broader reparative justice campaigns, including apologies, reparations payments, and other initiatives designed to promote social repair and reconciliation. In other cases, they have stood alone. In a few instances — Sierra Leone, for example — truth commissions have proceeded alongside prosecution efforts, but in most cases they have been convened in lieu of prosecution. In South Africa, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was empowered to award amnesty to perpetrators who testified before it as long as they met certain criteria, including a demonstrable political motive and full disclosure of their crimes.104

The Politics of Truth Commissions: The Latin American Experience

How well truth commissions succeed depends in large measure on the political circumstances in which they are appointed, a fact illustrated by the experience of Latin America, which has been the site of no fewer than ten commissions, most convened amidst transitions from military to civilian government. The earliest commissions, appointed to determine the fate of thousands of political opponents who “disappeared” during military rule, quickly ran up against the continuing political influence of military authorities and their elite allies. Several were forced to disband before they filed final reports, including the first one, the Bolivian National Commission of Inquiry into Disappearances, appointed in 1982. Argentina’s National Commission on the Disappeared, appointed in 1983, fared somewhat better. The commission’s report included information on some nine thousand disappearances, some of which was used to prosecute officers of the old junta. But growing opposition from the military and parliament forced the government to suspend the prosecutions. Under revised guidelines, officials in the military, police, and government were declared exempt from prosecution so long as they acted in accordance with the orders of superiors — precisely the defense rejected by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg four decades before.105

Some commissions were designed to fail. The Historical Clarification Commission of Guatemala was asked to investigate crimes committed over the course of a thirty-six-year civil conflict, but it was not given authority to subpoena witnesses or to name perpetrators in its final report. The National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation in Chile began in a similarly unpromising fashion. Charged to investigate human rights abuses between the military coup of 1973 and the restoration of civilian rule in 1990, the commission was hampered not only by the blanket amnesty that leaders of the old regime had given themselves but also by the fact that the former president, General Augusto Pinochet, remained commander in chief of the Chilean armed forces. Yet despite these obstacles, the commission succeeded in collecting fresh evidence about government crimes, which was later used to overturn the amnesty provision and prosecute some perpetrators. (Because they had disposed of victims’ bodies, chiefly by dumping them in the ocean, military officials were unable to prove that they had actually killed the people they kidnapped, making it possible to prosecute them for “ongoing sequestration,” a crime not covered by amnesty provisions or statutes of limitations.)106

The South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission

South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is the best known of recent international commissions and the one that best illustrates such institutions’ possibilities and potential limitations. Over a period of two years, the commission, which was chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, collected more than twenty thousand statements from victims of gross human rights abuse, as well as more than seven thousand amnesty applications from perpetrators detailing their crimes. Several thousand of these people testified in public hearings — hearings that were televised nationally and discussed in innumerable public and private forums. The commission’s report, along with volumes of supporting material, was widely distributed and is now an unerasable part of the historical record of the nation.107

But I feel what has been making me sick all the time is the fact that I couldn’t tell my story. But now I — it feels like I got my sight back by coming here and telling you the story.

Yet the South African process was not without flaws, as several speakers made clear. Many prominent political leaders refused to apply for amnesty or to testify before the commission, calculating (correctly) that the new government would not have the ability or will to prosecute them. The commission also interpreted its mandate in quite narrow ways, not only by confining itself to violations between 1960 and 1993 but also by limiting its attention to crimes that were “politically motivated” — crimes undertaken explicitly to defend or overthrow the apartheid regime. The effect of these decisions, as one speaker noted, was to focus attention on the struggle over apartheid and away from the inherent violence and depravity of the apartheid system itself. The creation of great wealth and great poverty; the denial of education; the destruction of families; the multifarious legacies of a half century of racially driven social engineering, coming on the heels of three centuries of colonialism: all these concerns fell outside the commission’s purview.108

Over a period of two years, South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission collected more than twenty thousand statements from victims of gross human rights abuse, as well as more than seven thousand amnesty applications from perpetrators detailing their crimes. The commission’s report, along with volumes of supporting material, was widely distributed and is now an unerasable part of the historical record of the nation.

Truth Commissions and Historical Repair

Yet as several speakers reminded us, the significant fact is not that truth commissions are imperfect but that they happen at all, that facts that in previous generations would likely have been forgotten or suppressed are today discussed and dissected in public forums. Obviously, commissions cannot by themselves repair the legacies of trauma and deprivation that crimes against humanity leave behind, but they do create clear, undeniable public records of what occurred — records that provide an essential bulwark against the inevitable tendencies to deny, extenuate, and forget. Perhaps most important, truth commissions offer the thing that victims of gross human rights abuse almost universally cite as their most pressing need: the opportunity to have their stories heard and their injuries acknowledged.109

One speaker sought to illustrate the value of truth commissions by posing a counterfactual question: What if the United States had convened a truth and reconciliation commission following the abolition of slavery in 1865? The question is both anachronistic and unanswerable, but worth pondering. Suppose that large numbers of formerly enslaved African Americans had been given a public forum to describe their experiences in captivity: decades of unremunerated toil; physical and sexual abuse; loved ones consigned to the auction block. Suppose that those who participated in and profited from the institution — a category that included slaveowners and non-slaveowners, northerners and southerners — were likewise asked to account for their conduct. And suppose also that these testimonies were broadcast widely, provoking public discussion and becoming enshrined in the nation’s collective memory — in textbooks and public memorials, political speeches and Hollywood films. Would the nation’s subsequent history have unfolded as it did? Would discussions about race provoke the misunderstandings and raw feelings that they so often provoke today?110

Truth Commissions in the United States

Though the United States has never formally convened a truth commission, the model has been used in more local contexts. The federal commission appointed to investigate the World War II internment of Japanese Americans is the obvious example, but truth commissions have also been established to examine injustices against African Americans. In 1993, the House of Representatives of the State of Florida funded a scholarly commission to investigate the 1923 Rosewood Massacre, a murderous assault on an all-Black town by a white mob following (false) reports of the rape of a white woman by a Black man. The legislature responded to the commission’s report by enacting the Rosewood Compensation Act, providing monetary compensation to families who had lost property in the attack and creating a small college scholarship fund for “minority persons with preference given to direct descendants of the Rosewood families.” (The legislature refrained from offering an apology.) More recently, two different cities in North Carolina launched truth and reconciliation initiatives: Wilmington, which created a commission to investigate the city’s 1898 race riot, essentially an armed coup against one of the last municipal governments in the South with substantial Black political participation; and Greensboro, which appointed a commission to investigate the 1979 massacre of Black union organizers by members of the Ku Klux Klan.111

While the North Carolina commissions have been widely praised for providing information and facilitating dialogue on painful chapters in the state’s history, the experience of the Oklahoma state commission appointed to investigate the 1921 Tulsa race riot was more mixed. The riot, which destroyed the most prosperous African American community west of the Mississippi, was one of the bloodiest in American history: an estimated three hundred Black people were killed and thousands more were driven from their homes by a white mob armed and deputized by local authorities. The commission succeeded in recovering the truth of an episode that had been completely erased from official histories of the city and state, but its significance as a vehicle of reconciliation was attenuated when the Oklahoma legislature, rejecting one of the commission’s primary recommendations, refused to appropriate money to compensate the small number of surviving victims. Bitter survivors responded by filing a class-action reparations lawsuit in federal court. The suit, Alexander v. Oklahoma, was dismissed in 2005 on statute-of-limitations grounds.112

Reparations: Theory and Practice

While most of the speakers entertained by the Steering Committee acknowledged the importance of redressing injuries, several warned of the danger of “commodifying” suffering, of defining claims to justice in narrowly material terms. Others spoke of the “one-time payment trap,” in which a single check is taken to absolve society of any further responsibility for injustice.

But if the basic principle of reparations is straightforward enough, the application of that principle in specific cases is enormously complex, as various speakers sponsored by the Steering Committee made clear. What form should reparations take? Who is entitled to receive reparations and who is responsible to provide them? How is the value of an injury to be calculated? What happens to reparations claims with the passage of time? Beneath these practical matters lay deeper moral and political questions. What are reparations intended to accomplish? Are they an end in themselves or one aspect of a broader process of repair and reconciliation? While most of the speakers entertained by the Steering Committee acknowledged the importance of redressing injuries, several warned of the danger of “commodifying” suffering, of defining claims to justice in narrowly material terms. Others spoke of the “one-time payment trap,” in which a single check is taken to absolve society of any further responsibility for the legacies of historical injustice.113

Determining the Medium of Reparation

The easiest reparations claims to understand, if not always to implement, are simple restitution claims — returning stolen property, looted artworks, sacred relics, and other such personal and cultural property to the rightful owners. Unfortunately, most cases of gross historical injustice do not admit of such tidy resolution. How does one make restitution for a human life or time in a torture chamber? In such circumstances, reparation must be made in some other currency. In the American case, the medium of choice is usually money, but there are abundant examples, in the United States and elsewhere, of reparations being paid in other forms, including land, education, mental health services, employment opportunities, preferential access to loan capital, even the creation of dedicated memorials and museums to ensure that a group’s experience is not forgotten by future generations. In the case of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, for example, the tendering of a presidential apology to the handful of surviving victims was accompanied by the commitment of federal funds to create a research center in biomedical ethics on the Tuskegee University campus.114

Pain can sear the human memory in two crippling ways: with forgetfulness of the past or imprisonment in it … too horrible to remember, too horrible to forget: down either path lies little health for the human sufferers of great evil.

What happens when those representing the interests of victims and perpetrators do not agree on the appropriate form of reparation? The history of Native American land claims illustrates the problem. Native Americans represent something of a special case in reparations theory, not only because of the scope of their injuries but also because of the existence of written treaties to undergird many of their historical claims. In 1946, the U.S. Congress, facing a raft of potential land disputes, created the Indian Claims Commission to hear and resolve all tribal claims against the United States, whether treaty-based or merely “moral.” The commission, which operated until 1978, was seen by its creators as a gesture of liberality, but it quickly became an adversarial body, enforcing strict eligibility standards and restricting awards to the minimum possible amount. The biggest bone of contention was the commission’s insistence that compensation be paid in money rather than land; to restore stolen land to its original owners, the commissioners reasoned, was both impractical and unfair to the land’s current owners, most of whom had purchased their property legally and in good faith. While many Indigenous nations accepted this logic, some did not, most notably the Sioux, who insisted on the actual return of ancestral lands in the Black Hills. With accumulated interest, the compensation awarded by the commission is today worth hundreds of millions of dollars, but the Sioux refuse to accept it, arguing that the Black Hills are sacred space and cannot be bought or sold.115

Calculating Compensation

Even where money is accepted as the medium of reparation, the question of determining the appropriate amount remains. Are such payments literally compensation, based on a calculation of actual losses, or are they more symbolic or broadly rehabilitative, in which case everyone in a given class should receive the same sum? The September 11 Victims Compensation Fund pursued the former approach. Created by Congress to forestall potentially crippling litigation against airline companies, the fund has dispensed some $3 billion, an average of about $1 million per family, to survivors of the men and women killed in the terror attacks of September 11, 2001. Obviously, the fund represents an unusual case in reparations history: the agency providing compensation, the U.S. government, was not responsible for the original offense; the perpetrators, Al Qaeda, have expressed no remorse for their crime nor any interest in repairing the resulting injuries. What makes the fund noteworthy here is both the size of the reparations and Congress’ decision to award different amounts to victims, based on income and a calculation of likely future earnings, a decision that ensured, in essence, that the largest sums went to the wealthiest families.116

Most recent reparations programs have taken the second, more symbolic approach. Under the terms of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, for example, all surviving victims of the Japanese American internment camps received $20,000, regardless of their actual losses in property and earnings. The sum of $20,000, in fact, has become something of a touchstone in the international reparations field. The government of Canada, which also interned citizens of Japanese descent during World War II, paid reparations in the amount of $21,000, reflecting the greater severity and duration of internment there. The private “atonement” money offered to surviving “comfort women” by the Japanese government in 2001 was the equivalent of $20,000, as was the sum recommended by South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission as reparations for victims of gross human rights abuse who had testified before the commission. (The amount eventually appropriated by the South African government was less than $4,000 per person.) $20,000 was also the sum recently offered to surviving First Nations children who were taken from their families and shipped to white mission schools in the Canadian counterpart to Australia’s forced racial assimilation policy.117

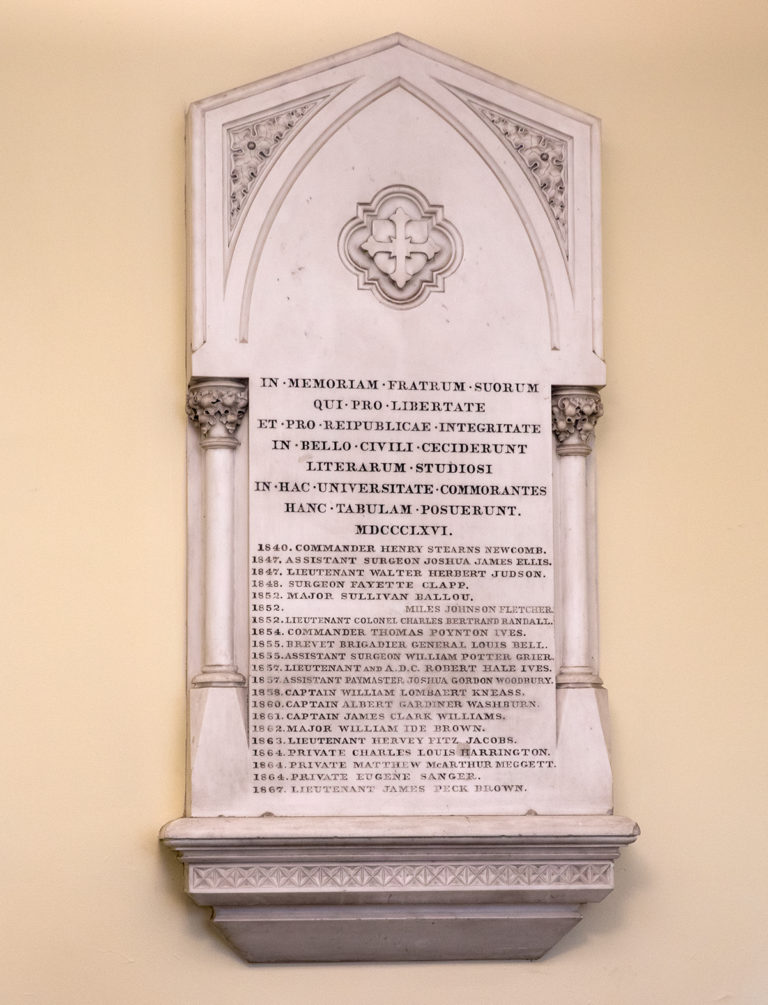

A memorial in Manning Chapel commemorates Brown University students who died fighting for the Union during the Civil War.

Reparations and the Holocaust

The conceptual and practical problems inherent in any reparative program are well illustrated by the sixty-year struggle over Holocaust reparations, a struggle in which Americans have played a leading role. In 1947, as the tribunal at Nuremberg completed its work, U.S. military authorities in occupied West Germany imposed the country’s first Holocaust restitution law, providing for the return of real estate, factories, and other property stolen from Jews as part of the Nazi’s “Aryanization” of the economy. American occupation officials also helped to draft the first model law for paying reparations to individual victims of Nazi atrocities, a step that many U.S. officials held out as a precondition for the restoration of German national sovereignty. In the years that followed, the West German government enacted a series of reparations programs, providing monetary grants and pensions to individual victims and their survivors, with prescribed payments for loss of life, loss of health, losses of property and professional advancement, and other specified injuries. American officials also helped to facilitate the 1952 treaty between West Germany and the state of Israel, providing for the transfer of 3.5 billion DM worth of money, machinery, and other goods to assist in the resettlement of Jewish refugees.118

Even with the memory of Nazi atrocities still fresh, many Germans objected to the idea of paying reparations. Critics decried reparations as victor’s justice, an exercise in guilt-mongering, even as a Jewish conspiracy against the German nation. In the early days in particular, opponents sought to undermine the program by imposing tight deadlines and strict eligibility standards, including, for a time, a requirement that victims prove that their injuries flowed from “officially approved measures.” Entire categories of victims were excluded from receiving reparations, including homosexuals, communists, and victims of the vast Nazi forced labor regime. Yet even admitting these limitations, the Holocaust programs represent the most ambitious social repair project in history. By the time of German reunification in 1990, the government of West Germany had dispensed some 80 billion DM in reparations, the bulk of it to individual victims and their survivors.119

Holocaust Litigation in American Courts

Half a century after the end of World War II, the Holocaust reparations issue was reborn in a new venue: American courts. In 1996, a class-action lawsuit was filed in federal district court in Brooklyn against the three largest private banks in Switzerland, charging them, in essence, with trying to defraud Holocaust victims and their descendants by refusing to release assets deposited in them prior to World War II. (Among other devices, the banks insisted that heirs produce death certificates for deceased account holders, a condition that was impossible to meet in the circumstances of the Holocaust.) Facing protracted litigation and a public relations nightmare, the banks settled the suit for $1.25 billion. In exchange, plaintiffs agreed to drop all future litigation against the banks, as well as the Swiss government and other Swiss corporations.120

Even at the time, there were some who saw the settlement more as a victory for the banks, which escaped future litigation for a relatively modest sum, than for Holocaust victims, the vast majority of whom received only token $1,000 payments. But the precedent had been set, and more than forty class-action lawsuits followed, all filed in American courts against private corporations alleged to have profited from Nazi atrocities. Most of the suits pertained to the exploitation of forced laborers, a group excluded from previous Holocaust reparations programs. At least ten million people were compelled to work in the Nazi war machine during World War II, including Jews (many of whom labored in a dedicated “extermination through work” program) as well as non-Jews. Fifty years later, more than a million of those people survived, as did many of the companies for which they had labored. Some of these firms had operations in the United States, making them vulnerable to suit in American courts.121

Viewed purely in legal terms, the German cases were considerably weaker than the Swiss bank cases. In 1999, courts in New Jersey dismissed suits against Ford Motor Company (whose German subsidiary had employed slave labor during World War II), Siemens, and several other major multinational firms, citing the expiration of statutes of limitations as well as the terms of the treaties ending World War II. But the barrage of bad publicity, as well as mounting pressure from American political leaders, prompted the companies to offer a settlement. According to the terms of the eventual agreement, German companies, with the assistance of the German government, made a one-time payment of $7,500 to surviving “slave” laborers, chiefly Jewish survivors of the extermination-through-work program, with smaller payments to other surviving “forced” laborers, chiefly Eastern Europeans. The entire settlement, including a fund for indigent survivors and a small “Remembrance and Future Fund” to promote Holocaust education, totaled about ten billion DM ($5 billion). In exchange, German companies and the German government were guaranteed “legal peace” from any further litigation in American courts. Appreciating the value of such an arrangement, the government of Austria and Austrian corporations immediately offered a forced-labor settlement of their own, valued at $500 million, or one-tenth of the value of the German settlement.122

Limits of Litigation

We shall return to the Holocaust reparations litigation, which served as the direct inspiration and model for a series of class-action lawsuits brought in the early 2000s by African Americans seeking reparations from American corporations alleged to have profited from slavery and the slave trade. In the present context, the Holocaust example is useful for illuminating the possibilities and pitfalls of litigation as a vehicle for pursuing reparations claims. As the Swiss and German suits showed, litigation often generates publicity, raising awareness of an injustice and increasing public pressure for action. Being linked to atrocious crimes can also be embarrassing to corporations, perhaps inducing them to settle. Should defendants refuse to settle, however, the impediments to successful reparations litigation are enormous, at least in American courts. As several of the speakers invited to Brown by the Steering Committee noted, reparations lawsuits, whether directed against the federal government or private corporations, face a host of procedural hurdles before they can even be heard on the merits, including the government’s sovereign immunity from suit; expired statutes of limitations; problems of establishing standing and a justiciable case (essentially, the need to establish a link between a specific injury in the past and a specific plaintiff in the present); and the so-called “political questions” doctrine (the idea, first articulated by John Marshall in the 1820s, that courts have no business intervening in matters properly belonging to the legislature). Some of these obstacles might be overcome: Congress has the authority to waive sovereign immunity and extend statutes of limitations; courts can be more or less strict in interpreting standing or the meaning of political questions. But in the present political circumstances, it is very difficult to imagine lawsuits seeking reparations for slavery or other historical injustices making any headway in American courts.

Some speakers questioned not only the practicality but also the wisdom of pursuing historical redress through litigation. While acknowledging that reparations suits are often filed as a last resort, these speakers suggested that courts of law, with their inherently adversarial structure, their focus on past injuries, and their narrow conceptions of “injury” and “settlement,” are precisely the wrong venue for promoting reconciliation and a better future.

Some of the scholars invited by the Steering Committee went further, questioning not just the practicality but also the wisdom of using litigation as the medium for confronting questions of historical injustice and social repair. While acknowledging that reparations suits are often filed as a last resort, these speakers suggested that courts of law, with their inherently adversarial structure, their focus on past injuries, and their narrow conceptions of “injury” and “settlement,” are precisely the wrong venue for promoting reconciliation and a better future. Not only does litigation risk pulling people into the “one-time payment trap,” but it also creates no opportunity for dialogue, for the descendants of victims and of perpetrators to exchange perspectives and to develop shared understandings of their past experience and present predicament. Such speakers were certainly not disavowing reparations per se, or the moral and political urgency of confronting legacies of injustice, but rather attempting to move a debate currently waged on narrowly legalistic grounds onto the broader terrain of history, memory, and moral obligation.123

Reparations Claims and the Passage of Time

Every exercise in retrospective justice is unique, as are the horrors that prompt it. Yet great historical crimes have at least one thing in common: all direct participants, both perpetrators and victims, eventually die. Their passing raises one final, thorny set of questions. What happens to reparations claims with the passage of time? Are the descendants of victims of gross human rights abuse ever entitled to redress (as they would be, say, in the case of a stolen painting) or do all such claims die with the original victim? Is the responsibility to make reparation ever handed down, or is that obligation also expunged after one generation? What about crimes — such as slavery and the transatlantic slave trade — that produced great wealth? Are the descendants of those responsible free to enjoy the fruits of injustice simply because they took no part in the original offense? All of these questions have both legal and ethical dimensions. They also have obvious relevance to the current American debate over reparations for slavery, an institution that ended in the United States before all currently living Americans were born.

As vexed as reparations claims involving living victims can be, the conceptual and practical problems presented by multi-generational cases are far greater. But there are also obvious problems with limiting one’s moral and political concern to “current” injustices. Not only does such a standard ignore the profound and lasting legacies of crimes against humanity, but it also invites societies emerging from atrocious pasts to temporize.