Fortunately for me, historians are paid to interpret the past, not predict the future. The re-publication of the Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice prompted this revelation, as I reflected on my own expectations nearly fifteen years ago, at the time of the Report’s initial appearance.

If you had asked me twenty years ago whether the Confederate battle flag would ever be removed from the South Carolina statehouse grounds, whether John C. Calhoun’s name would no longer adorn a Yale University residential college, whether Aunt Jemima would cease to smile from the packaging of pancake mix, whether reparations for slavery would figure in the Democratic Party’s presidential debates, I would have said no. I would have been very confident in the refusal of white America to jettison its treasured symbols and the collective memories that embed racial dominance in the quotidian experience of everyday life. There was no way that businesses would abandon their lucrative brands, let alone confront the slaveholding skeletons in their corporate closets. No public reckoning with slavery could be possible amidst the so-called “culture wars” of the early 2000s.

But if you asked me at that same moment whether the percentage of Black faculty and students was likely to increase substantially at Brown, whether the prevalence of police killings of Black men and women was likely to decrease, or whether the courts could be counted on to enforce civil rights laws, I would probably would have given a more optimistic yes. Institutions like universities and governments could be counted on to create a better and more inclusive future through thoughtful policymaking, and even amidst the political outrages of the Bush-Cheney administration, I remained confident that the arc of history would indeed bend toward justice. Such hopes soon bore witness to the election of Barack Obama to the presidency on a November evening in 2008, when Brown undergraduates gathered joyfully on the Rhode Island State House steps to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Clearly, I’d gotten things wrong, and, in retrospect, perhaps should have known better, since symbolic sacrifices in the aisles of the grocery store are easier concessions than the dismantling of systemic racism. I should not have been surprised by the ferocious ethno-nationalist “whitelash” to a two-term Black president that has characterized almost the entirety of the 2010s and endures to this day.

That said, I don’t want to minimize the gains that come from not having to see J. Marion Sims venerated in Central Park, from not having to attend a North Carolina high school named for a Confederate general, and from not having commercial websites like The Knot promote former slave plantations as romantic wedding sites. Nor is it without significance to find a memorial to the victims of slavery on the grounds of the University of Virginia, to see a film like Twelve Years a Slave win Oscars, and of course, to visit the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall in Washington, DC. The symbolic landscape matters a great deal, whether for eliminating the harms of white supremacy’s built environment or constructing the kinds of inclusive public spaces that might provide the infrastructure for an anti-racist future.

If historians aren’t great at predicting what’s ahead, we are nonetheless committed to the idea that the stories we tell about the past have some bearing on the futures we can (or cannot) collectively imagine. Certain modes of doing history can provide legitimacy to the status quo and serve to make present-day inequalities appear incontestable. Other modes of doing history are predicated on recovering resistance, dissent, and struggle as a testament to the fact that the past was full of paths not taken to the present, the knowledge of which emboldens us to jettison a paralyzing fatalism and recognize our present as something other than inevitable. And yet other modes of history sit at the intersection of reckoning and healing — a faith that if we tell the truth about the past in all its deromanticized, demystified complexity (warts and all, as the saying often goes), we can move beyond trauma, shame, and denial toward a world in which everyone can thrive and prosper. This would position historical truth-telling as a form of repair, first by ceasing to do any additional harm in the form of incomplete and misleading accounts of what happened in the past, and then by providing the basis for a substantive transformation of society on the premise that the truth will set all of us — the descendants of survivors, victims, perpetrators, beneficiaries, bystanders, witnesses, and innocents — free.

Re-reading the Slavery and Justice Report in 2021, I am struck by its embeddedness in this last tradition and the expectation that a full, honest engagement with the American past would facilitate a different and better American future. This was perhaps also unduly optimistic. Telling the truth about history is a necessary, but insufficient, condition for structural transformation. Any anti-racist future requires it, but it alone cannot create that future. The last fifteen years bear witness to this in complicated ways — not in ways that diminish the Slavery and Justice Report or the spirit in which it came into being, but rather in ways that demand perhaps more utopian thinking rather than less.

The American confrontation with slavery and its legacies accelerated dramatically over the last two decades. “America has slavery on the brain these days” wrote New York Times columnist Charles Blow in 2013, taking note of the increasing visibility of slavery in films and public discourse. But Blow was also keenly aware that “the pillars of the institution — the fundamental devaluation of dark skin and strained justifications for the unconscionable — have proved surprisingly resilient.” Blow warned against seeing “progress” when it remained so clear slavery’s “poison tree continues to bear fruit.”1 The subsequent eight years have borne this out in alarming ways, especially in the devaluation of Black life. Indeed, we are left to confront the uncomfortable relationship between anti-Black violence and the remediation of the symbolic landscape. Why have Confederate monuments come down? Why have Uncle Ben and Rastus the Cream of Wheat Chef left the supermarket aisles? It isn’t because we have told the truth about the past. The precipitating events were shocking murders, not scholarly monographs. Reckonings — always incomplete, but reckonings nonetheless — followed the events in Ferguson, Charleston, Minneapolis. Things happened after a police officer shot Michael Brown; after a white supremacist shot nine worshippers at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church; after a police officer suffocated George Floyd on a city street. This is a dynamic we know from life at American colleges and universities as well: buildings are renamed after the false arrest of a student of color; a new diversity curriculum is mandated after racist graffiti appears on a dorm wall.

Of course, it doesn’t make any sense to say that George Floyd’s murder caused American corporations to jettison beloved and valuable, if racist, trademarks in the summer of 2020. Mass protests and state violence — millions of Americans in the streets declaring Black Lives Matter, met by the disproportionate force of armed police units — made it impossible to maintain the status quo. Millions of people engaged in civil disobedience, millions of people engaged in acts of solidarity with neighbors and strangers alike, millions of people engaged in speech acts large and small, from the Black high school students who led Providence in peaceful protest to the white families that put “Black Lives Matter” signs up in their predominantly white neighborhoods. Business leaders, university presidents, and public officials ascertained the direction the wind was blowing, and they chose this moment to seek a fuller accounting of slavery’s legacies and afterlives. But none of this happened without advocates for justice taking to the streets and demanding an end to police killings of Black Americans. Revelations of righteousness on high rarely occur absent pressure from below.

One might tell the story of Brown’s slavery and justice undertaking in a similar, if less dramatic, fashion. Black activists in the 1990s rekindled a conversation about reparations for slavery, filing a federal lawsuit against the insurance company Aetna for issuing policies on the enslaved. They formed groups like the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, and mobilized prominent legal scholars like Harvard’s Charles Ogletree to identify other possible targets for civil litigation. These would have to be “legacy” firms or institutions whose present-day wealth could be traced directly to slavery-era activity. Brown University was an obvious defendant in light of the fact that the “founding family” whose name adorns the institution had been active in the eighteenth-century Atlantic mercantile economy. Meanwhile, here on campus, student activists declared their unwillingness to see a demeaning advertisement circulate in the Brown Daily Herald. In the name of free and open debate, an entrepreneur of outrage bought space in the student newspaper to suggest that, among other things, slavery had been of long-term benefit to African-descended people in America. Student activists made sure that that issue of the BDH did not circulate, which then generated the predictable (and to some, desirable) outcome of great hand wringing over campus speech and “political correctness.” By most accounts, President Ruth J. Simmons was motivated to form a campus investigative committee in response to a looming reparations lawsuit on the one hand and this incident of campus activism on the other. Both can be understood as pressure from below.

Just as Brown was initiating its self-study, a conversation was emerging within the scholarly literature around “slavery and memory,” as part of a larger move toward the emergence of “memory studies” and “public history” as discrete fields of inquiry. The former stressed the importance of the past to collective identity formation, while the latter was predicated on the idea that most historical learning takes place not in the pages of a book but rather in the public space of markers, museums, and movies. Clearly there was something to be said for studying not what happened in the U.S. before 1865, but what happened in the century and a half that followed, to amplify or suppress our collective understandings of that past. The stories that get told about what slavery was or wasn’t matter to how Americans understand themselves as insiders or outsiders within the culture. The prevailing public understanding of the causes of the Civil War have enormous consequences for the national project. As a result, scholars delved into the efforts of museums and tourist destinations like Colonial Williamsburg to reflect the experiences of the enslaved. They interrogated the twentieth-century proliferation of Confederate symbology (“the Rebels” as a popular sports mascot, for example) far beyond the South. They analyzed textbooks, deconstructed films and television shows, and, critically, located the politics of white supremacy in the nation’s landscape of memorials and monuments.

A number of Brown undergraduates entered this project through a “Slavery and Historical Memory” course I began teaching at Brown beginning in 2002 and that ran concurrent with the Slavery and Justice Committee’s undertaking. Although we read about topics familiar to any professional historian of the United States, the material in the course came as a surprise to most of the students in the class. It was, like most classes at Brown, predominantly white-enrolled. It was a class for students in their very first semester of college, and students brought the cultural horizons of eighteen-year-olds — up on the latest Dave Chappelle sketch, immersed in Aaron McGruder’s comic strip, The Boondocks, but not knowing about James Forman’s reparations claims in the 1960s, and not having seen Roots in the 1970s, but maybe having read a Toni Morrison novel in high school. The students who enrolled in the course were largely products of the American education system’s inadequate capacity to address slavery.

The course was designed to think about power and the production of the past: Who had the power to make their version of events real? To label events? To embed them in textbooks and to memorialize them in public spaces? To shape the law? To have their pain acknowledged? The course concluded with such now-canonical work as Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, Nell Irvin Painter’s “Soul Murder and Slavery” essay, Nathan Huggins’ “Deforming Mirror of Truth” article, and Annette Gordon-Reed’s dismantling of the legend that claimed Thomas Jefferson hadn’t fathered Sally Hemings’ children. It took a deep dive into narratives of a specific historical event — Nat Turner’s 1831 slave insurrection in Virginia, running from Turner’s own purported “Confessions” and William Styron’s stylized re-imaginings of that moment, to Sherley Anne Williams’ rejoinder in Dessa Rose, and Robert O’Hara’s queering of the Turner story to confront AIDS and the oppression of the closet in Insurrection: Holding History. The course looked at racist marketing and plantation tours, and picked up the reparations debate just then revitalized by Randall Robinson’s The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks. One year, the course came with a movie series too, expanding beyond the U.S. to consider Gillo Pontecorvo’s Queimada (1969) and Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s La última cena (1976), as well as Haile Gerima’s Sankofa (1993) and Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (2000).

The pleasure of the course, for me as the teacher, was having students — regardless of their backgrounds — convey the righteous indignation of realizing that they had been told lies for the previous eighteen years of their lives. Of seeing students grasp analytical language to give power to what had previously been inchoate feelings or sensibilities. Of seeing scales fall from the eyes of other students who had never been asked to see what was obvious all around them. In some ways it felt too easy: so long as America was profoundly in denial, so long as Black stories still remained cordoned off in the “diverse perspectives” boxes of textbook pages but not in the main text, so long as racist representations of slavery continued to appear in advertisements and film, teaching this class would be a slam dunk.

It wasn’t. The engagement of slavery and memory was accelerating with such a speed that students showing up for the class in 2011 and 2013 were armed with a completely different sensibility and a more powerful set of analytical tools. Sure, it was still amazing to put Charles Mills’ The Racial Contract in front of them, to share Kyle Baker’s graphic novel on Nat Turner, and to think with Saidiya Hartman’s powerful Lose Your Mother. But the starting point — that the history of slavery, its telling or suppression, and its representation in public space are crucial to the present-day politics of race — was no longer so revelatory, even for students who arrived on campus shrouded in white privilege. Fewer students were coming to Brown feeling like they’d been lied to their whole lives about slavery. And indeed, a more honest conversation about slavery in popular culture, in school curricula, and in museum exhibitions had emerged, albeit as likely to have been precipitated by Black suffering and death (e.g. during Hurricane Katrina) as by enlightenment occasioned by the election of the first Black president. Although the Confederate flag still flew in places, Brown undergraduates — Black and white — were cautiously optimistic that such gratuitous violations of our shared sensibilities would be remedied in due course.

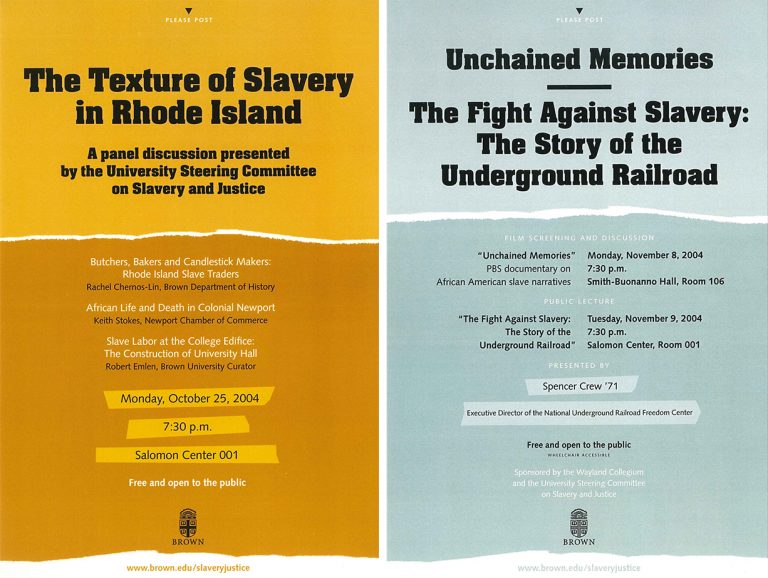

President Ruth J. Simmons charged the Steering Comittee on Slavery and Justice “to help Brown organize its impressive intellectual resources and to supplement them with outside expertise where necessary … ” The various public programs sponsored by the Committee, such as this panel discussion and film screening, created awareness, according to the Report, “of a history that had been largely erased from the collective memory of [the] University and state.”

I would like to think that Brown’s Slavery and Justice Report had something to do with this. Its impact is not easily assessed. The Report’s publication did not convince Rhode Island voters to drop “Providence Plantations” from the state’s name in a 2010 referendum (although they would eventually do so in 2020). It did not keep Raymond Kelly, the architect of New York City’s racist discretionary policing, from being invited to speak on campus. It did not pull the percentage of Black faculty and students at Brown into double digits. It did, however, mobilize many colleges and universities to see that it was possible to look directly into the slaveholding past and assert an institutional responsibility for that past; it brought a different landscape of memory to campuses like Brown’s, where a memorial to the victims of the Atlantic slave trade now sits on the Front Green, also known as the Quiet Green.

This was before Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, Philando Castile, or Breonna Taylor. Before #BlackLivesMatter became the requisite hashtag to repudiate callous acts of police violence that suggested that Black lives did not. Of course, racist police violence was not new. But thanks to the cell phone camera, it became visible to an ever-growing segment of the American population, including those not living it on a daily basis. Thanks, too, to a generation of scholarship on mass incarceration and its antecedents in a prison-industrial complex that dated to the nineteenth century, there was a new language available to think about plantations, penitentiaries, and the historical continuities that created “slavery by another name.”2 Increasingly, students were speaking of slavery and its afterlives and its legacies — a far more powerful term than “memory” for recognizing centuries of structural racism that, thanks to journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones and her New York Times collaborators, an increasing number of Americans now date to 1619.3

At the same time, many students had been disabused of the cautious optimism I had sensed in the four or five years following the release of the Slavery and Justice Report. The United States had not, in fact, become post-racial, and the presence of Black presidents — whether at Brown University or in the White House — proved inadequate for the task of dismantling structural racism. More distressingly, police killings of unarmed Black men and women continued unabated, calling protestors into the streets again and again to demand redress. These protests have been powerful, although regrettably less effective in stopping police violence than in compelling corporations to change their brand logos and motivating college and university administrators to undertake new initiatives to combat anti-Black racism on campus. It speaks to a profoundly disturbing dynamic that Caleb E. Dawson, a graduate student at UC Berkeley, frames the question in the starkest terms: “Why does it feel like Black death is a prerequisite of change in how Black lives matter at/to a university?”4

I’ve wondered about teaching the slavery and memory class again. On the one hand, it would still be predominately white-enrolled, and some students would invariably come to ask questions about a misleading plaque in the square of their hometown or whether Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton botches the history of slavery despite its provocative color-conscious casting. But on the other hand, as a much longer tradition of scholarship in fields like Africana Studies has made clear, as Black feminist authors have hammered home in their scholarship, as activists and abolitionists in the streets have insisted, the temporalities of now and then are not everyone’s lived experiences; the boundary between slavery and memory are too unstable, the legacies and afterlives too powerful to cordon off in a class. But even more, they are too expansive to contain in a semester, too encompassing to limit to the weeks of a syllabus, and indeed, too urgent to be studied as though this were a history past. This is a history we still live inside, not a history we have the luxury to “remember.”

The year 2021 may not be the optimal moment for reflecting on the Slavery and Justice Report. Amidst a global pandemic in which Black mortality rates are disproportionately high and in which some substantial percentage of the American population denies the existence of COVID-19 altogether, telling the truth about a university’s past seems quaint, or even self-indulgent. In the wake of the summer 2020 mass protests that brought down statues, renamed buildings, and even prompted Juneteenth holidays for employees at major firms, is there any reason to believe Black citizens will be safer in their encounters with law enforcement? Alternatively, 2021 may be the optimal moment, as it forces us to recognize the entanglements of anti-Black violence and subsequent efforts toward remediation — a dialectic of racist violence and anti-racist remediation that pulls us forward without offering any assurance of obliterating the former and achieving the latter. Yet to the extent that we are caught in this nexus, we are also reminded of the power of common people, acting in concert and in public space, to wield the necessary pressure from below to push the process forward.