Tactility, Memory Work, and Martin Puryear’s Slavery Memorial

I have long admired Martin Puryear’s sculpture, attracted to his material surfaces and spare forms. Puryear is a maker of objects, an artist known for the ways in which he engages with materials, employs traditional woodworking methods, and sees the potential for rich psychological, emotional, and sensorial associations with his creations. He has described his work as being about the maker and the materials: “I would say I’m interested in making sculpture that tries to describe itself to the world, work that acknowledges its maker and that offers an experience that’s probably more tactile and sensate than strictly cerebral.”1 I first encountered Puryear’s work in a 1992 exhibition at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC.2 In the spacious, white-walled galleries, Puryear’s objects challenged me to rethink my understanding of what sculpture could be: the ingenious balance of Circumbent (1976), the dark luminous shape of Self (1978), the evocative suggestion of time in Night and Day (1984), and the sacred biomorphic form of Sanctum (1985).

I rehearse this first encounter with Puryear’s sculpture because it shapes how I understand Slavery Memorial (2014) at Brown University. The tactile and sensate are key to understanding the memorial, as is its location on the Front Green, also known as the Quiet Green, and the memory work that it both does and does not accomplish. Puryear has called the memorial “something in the nature of an industrial artifact,” referencing the technology of the ball and chain used to shackle enslaved persons as representative of the industrial reality of slavery.3 The materials of this artifact — ductile cast iron in a rich rust-brown patina, an impact- and fatigue-resistant industrial material — bring into the present the palpable brutality of slavery and Brown’s connection to this slave past. According to Lisa Blee and Jean M. O’Brien, memory work indicates “the myriad ways in which monuments imbedded in a social fabric play a role in how individuals and collectivities make meaning of the past as distinct from the concrete matter of what actually happened.”4 The concrete historical details of Brown’s ties to the slave trade and the use of enslaved labor on campus are outlined in the Slavery and Justice Report. In its location on the Quiet Green, the memory work of Slavery Memorial is dynamic and multivalent, asking the diverse members of Brown’s community to contemplate over and over again their physical connection to the past in the context of the everyday.

Martin Puryear’s Slavery Memorial is located on Brown’s Front Green. On September 27, 2014, President Christina H. Paxson addressed more than 300 University guests who had assembled for its dedication, asserting "The reason this memorial is in such a prominent spot on our campus is that we know a polite remembrance is not enough. We have an obligation, here at this citadel of free speech, to set a higher standard...."

In the early twenty-first century, U.S. colleges and universities have begun to wrestle with the historical role of slavery at their institutions.5 Several of these institutions have actively engaged the memorialization process and commissioned monuments for their campuses: Unsung Founders Memorial (2005) at the University of North Carolina; Slavery Memorial (2014) at Brown University; Baldwin Hall Memorial (2018) at the University of Georgia; Memorial to Enslaved Laborers (2020) at the University of Virginia; and Commemorative to Enslaved Peoples of Southern Maryland (2020) at St. Mary’s College. With careful thought and consideration, the memorials are reminders of the deep ties these institutions had to slavery, and they serve to confront the slave past in the present through three-dimensional form and interventions into the hallowed spaces of each campus.

Brown University set the stage for the serious consideration of the University’s relationship to the transatlantic slave trade and slavery with the establishment of the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice. The University’s efforts to reconcile its slave past came directly from the first African American president of an Ivy League institution, Dr. Ruth J. Simmons. In April 2003, Simmons formed its committee to study the issue of reparations for slavery, the relationship of the slave trade to the University’s early benefactors, and the role of slavery at Brown and more broadly in Providence and the state of Rhode Island. From the beginning, Simmons called for the organization of informed and, at times, difficult public conversations about the slave past.6 In 2006, the Slavery and Justice Committee issued its final Report, recommending that, among other things, the University memorialize its “entanglement with the transatlantic slave trade” with a physical monument, “a living site of memory, inviting reflection and fresh discovery without provoking paralysis or shame.”7

In 2007, Simmons appointed the Commission on Memorials, a ten-member committee that included faculty, administrators, alumni, undergraduate and graduate students, and local Providence leaders. After meeting throughout 2007–2008, the Commission recommended in 2009 “that the Public Art Committee of the University be asked to commission a memorial that recognized the University’s ties to slave trading, and, as part of the process, the Committee should engage with the wider campus and Rhode Island communities.”8 Brown’s Public Art Committee, which included faculty, alumni, a student, and local arts leaders, considered more than sixty-five artists, architects, and landscape architects for its memorial. Five finalists were invited to present their potential approaches to the project. The funding for the memorial came from the Corporation of Brown University, the governing body responsible for setting the budget, siting buildings, and establishing policy and strategic plans for the University. In February 2012, the Public Art Committee announced that it had selected the celebrated American sculptor Martin Puryear “for his thoughtful discussion and commitment to the significance of the memorial.”9 According to Puryear, he felt an overwhelming sense of responsibility to address the “historical truth” of slavery, asking himself, “How do you use your art to somehow do justice to that historic truth?”10

On April 3, 2015, I visited Brown’s campus for the first time. I drove up with a colleague from New Haven to photograph the monument for my research. We arrived in the late morning on one of those brisk days with slight warmness, alerting us to the arrival of spring. We entered along a path leading from University Hall to Carrie Tower. From a distance, Slavery Memorial seemed small in relationship to the architecture surrounding it and the narrow expanse of the Quiet Green. As we drew near, I was struck by the two distinctive parts of the monument: the cast iron dome and broken chain with mirrored-surfaces and the gray and black stone plinth with engraved text.

Puryear’s memorial evokes a ball and broken chain sinking into the Earth: “I chose to create the work in iron, ductile cast iron, an industrial material. . . . [It] is not brittle like gray iron. It’s much more resilient and robust. It’s designed to last as long as any building on this campus.”

Up close, Slavery Memorial’s tactile connection to the ground is remarkable. The half dome, measuring eight feet in diameter, appears to be half buried in or emerging from the earth, depending on one’s perspective. Its rootedness in the earth of the Quiet Green suggests that Slavery Memorial is pushing up through history, asking for recognition of the painful past. According to the artist, the memorial is an artifact “partially buried — mostly buried — but that will never, ever disappear from memory.”11 The allure of the monument is its low scale; the surface qualities of rusted iron and mirrored surfaces also elicit interactions and touch. During my visit in 2015, muddied shoe tread marks covered the dome — clearly people had walked across the memorial — and a group of students lounged on the memorial. Initially, I was shocked and disappointed in the behavior and with the visual evidence.12 I also realized that no signage prescribed how Brown’s community was to interact with the memorial. Did the footprints represent a deliberate attempt at the erasure of memory? I’m not sure; perhaps they indicated facetious disregard for the memorial’s conveyed meaning or a resistance to the University’s declaration of the importance of the memorial. On a return visit in spring 2019, I noticed a new sign asking for the community to respect the boundaries of the memorial, setting it apart as a “sacred object.” As a hallowed artifact, we are now meant to ignore its material call for us to touch.

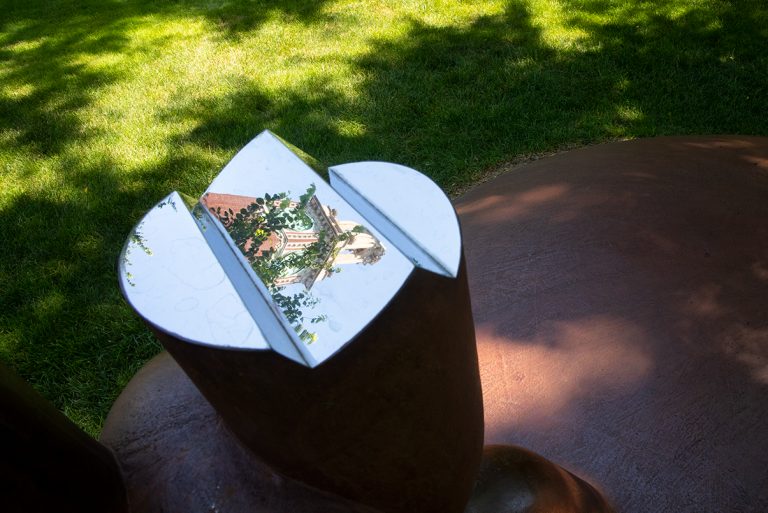

Although touch is restricted, the sensate is realized through the strange beauty of the upward sweep of the chain and the use of mirror-polished stainless steel on the end of the broken links of the chain. In both a visual and bodily experience, I found myself fully immersed in the memorial through the reflective surfaces of the jagged ends. The play between permanence and seasonal change captured my attention. On that April day, filled with cerulean skies, the mirrors captured the movement of trees, clouds, and buildings: University Hall, Manning Hall, and Carrie Tower waver in and out of view, reminding us of the long history of Brown and the economics of the transatlantic slave trade that helped to fund the University. The mirrored surfaces reflect the change of time and seasons, but also mark the permanence of these buildings, and in the case of University Hall (1770), remind us of the enslaved labor used to construct the oldest building on campus.

The ends of the broken link are finished to a mirror-like surface, reflecting sky, sun, trees, life. Slavery Memorial is both immediately accessible — “a blunt monument,” Puryear called it at the 2014 dedication — and open to extensive observation, reflection, and interpretation. "After I took on the project, I realized what a weight it was to try to memorialize something as shameful as the practice of buying and selling human beings, which went on for so long in this country. . . . It was a very, very overwhelming sense of responsibility to historical truth."

The second part of the memorial is a stone plinth, with a carefully worded text. It reads, “This memorial recognizes Brown University’s connection to the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the work of Africans and African Americans, enslaved and free, who helped build our university, Rhode Island, and the nation.” The marker also contextualizes the memorial: “In 2003 Brown President Ruth J. Simmons initiated a study of this aspect of the university’s history. In the eighteenth century slavery permeated every aspect of social and economic life in Rhode Island. Rhode Islanders dominated the North American share of the African slave trade, launching over a thousand slaving voyages in the century before the abolition of the trade in 1808, and scores of illegal voyages thereafter. Brown University was a beneficiary of this trade.” Puryear has noted that he and the Public Art Committee went through a number of iterations of the text. “For me, the most complicated part was finding the right tone that this project should take. It had to avoid blame and moralizing. It simply had to present the facts.”13 Although I fully understood the need for interpretive text, the current inscription does not effectively convey the depth of Brown’s process to examine its slave past nor does it fully acknowledge the profound financial gains of Brown’s entanglement with the slave trade.

Seeing Slavery Memorial for the first time also called to mind Driss Sans-Arcidet’s Fers (2009), which I had seen the previous spring in Paris. Sans-Arcidet (alias Musée Khômbo) created a monumental manacle for la place du Général-Catroux in the 17th arrondissement — two large, rusted iron cuffs with chains. The artist left one cuff closed with broken chains pointing to the sky, the other cuff open with the chains touching the ground. Although the monuments share a common visual language, Sans-Aricdet’s Fers and Puryear’s Slavery Memorial are fundamentally different in their motivations. Fers is a monument dedicated to General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas (1762–1806), who was born to an enslaved Haitian woman and white French nobleman, was the first man of African descent to become a brigadier general in the French army, and was the father of the famed Alexandre Dumas, author of The Three Musketeers (1844) and the Count of Monte Cristo (1844–1846). The manacles are supposed to represent Dumas’ childhood in slavery (the closed iron), then his freedom and contribution to society (the open iron).14 Puryear’s memorial, of course, is not dedicated to an individual. Rather, it works to settle slavery into memory at Brown and to point to future work for social justice and equity.

Slavery Memorial’s location is important for its historic significance as the site of the University’s oldest building, and the entrance point for Brown’s Convocation and Commencement. I understand Slavery Memorial as both a marker of remembrance and as a teaching tool engaged in memory work. Marita Sturken points out that “monuments are a form of pedagogy; they instruct on historical values, persons, and events, designating those that should be passed on, returned to, and learned from.”15 In her dedication remarks, current President Christina H. Paxson argued forcefully for the placement of the memorial on the Quiet Green and the pedagogical work that the memorial could do for the community: “The reason this memorial is in such a prominent spot on our campus is that we know a polite remembrance is not enough. We have an obligation, here at this citadel of free speech, to set a higher standard. We need to commit fully to the act of remembrance. We need to weave it into the daily rhythm of Brown University, and into all of the forms of work that we do on this campus. We must reject the forms of injustice that so freely circulated in 1764, and which have not disappeared nearly as neatly as we would like.”16 President Paxson drew analogies between Brown’s efforts to recognize its slave past and the fight against the modern legacies of slavery, including human trafficking, permanent servitude, and inequities in access to housing and healthcare in the twenty-first century, presenting an expansive understanding of Slavery Memorial’s memory work.

Two student accounts — one for a student-run magazine (2014), the other an undergraduate honors thesis (2019) — make meaning from the monument in very different ways and serve as counterpoints to the administration’s view of the memorial. Writing for Bluestockings Magazine in 2014, two self-identified Black students, Malana Krongelb and Justice Gaines, assert that Slavery Memorial does not acknowledge the humanity of the enslaved persons who labored at Brown: “This Memorial glosses over the experiences of Black people and instead privileges the perspective of white slave owners and beneficiaries of the trade. It twists the slavery narrative as only meaningful for capital gain: in this case, Brown’s financial foundation. The Slavery Memorial thereby silences the humanity, culture, and resistance present among Black communities in slavery-era Rhode Island. It ignores the presence of Black members of the Brown community today, perpetuating how this predominantly white institution has produced centuries of silence.”17 For these students, the memorial is a failure because it assuages white guilt and offers no institutional apology for slavery.

As part of her research for her undergraduate honors thesis, Kayla Hill conducted a survey of Brown undergraduate students to assess their feelings about the memorial. Hill noted the conflict some students felt over the design, the motivation for the project, and inappropriate interactions with the memorial: “One student remarked that the design is almost ironic in that it highlights how much of the impact and legacy of slavery is still buried and hidden by the university, despite the university commissioning a memorial; another student felt that the project seems more invested in being a relic of history instead of grappling with the university’s continued enactment of the same violence it perpetrated in past centuries.”18 Both Krongelb and Gaines’ response and Hill’s findings point to the ways in which memory work is often contested and contentious, reliant not on the past but on current pressing problems and conditions.

As Blee and O’Brien suggest, “Monuments can, by virtue of their design, accomplish many kinds of memory work simultaneously. Because granite and bronze monuments appear permanent and unshifting…they can bring a core identity to a place. But once fixed in a landscape, monuments become enmeshed in the complexities of life that are in constant change.”19 Slavery Memorial presents Brown University’s community with the ongoing challenge to reflect on its slave past and to consider this history in the context of the life of the campus. As Anthony Bogues, director of the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, noted at the dedication, “A memorial is not only a marker that creates pause, that makes us say, ‘That’s done.’ A memorial is also about things to do, recognizing work done but beckoning us forward.”20 Slavery Memorial permanently marks the ground of the Quiet Green while its meaning is constantly reshaped depending on where one stands, metaphorically, in relation to it.

Julian Bonder, one of the co-creators of Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery (2012) in Nantes, France, uses the term “working memorial” to describe the project of encouraging collective engagement and active dialogue.21 He proposes that the role of the artist and architect in creating memorials is to uncover and anchor histories and memories and to create dialogue. “Neither art nor architecture can compensate for public trauma or mass murder. What artistic and architectural practices can do is establish a dialogical relation with those events and help frame the process of understanding,” argues Bonder.22 With the University’s recent decision to select the Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice for the First Readings program for incoming first-year Brown students, Slavery Memorial has work to do — to engage the campus about its legacy of slavery and to point a way forward through dialogue and action on the “infinite possibilities of freedom.”23